Mountain of the Dead

Mountain of the Dead

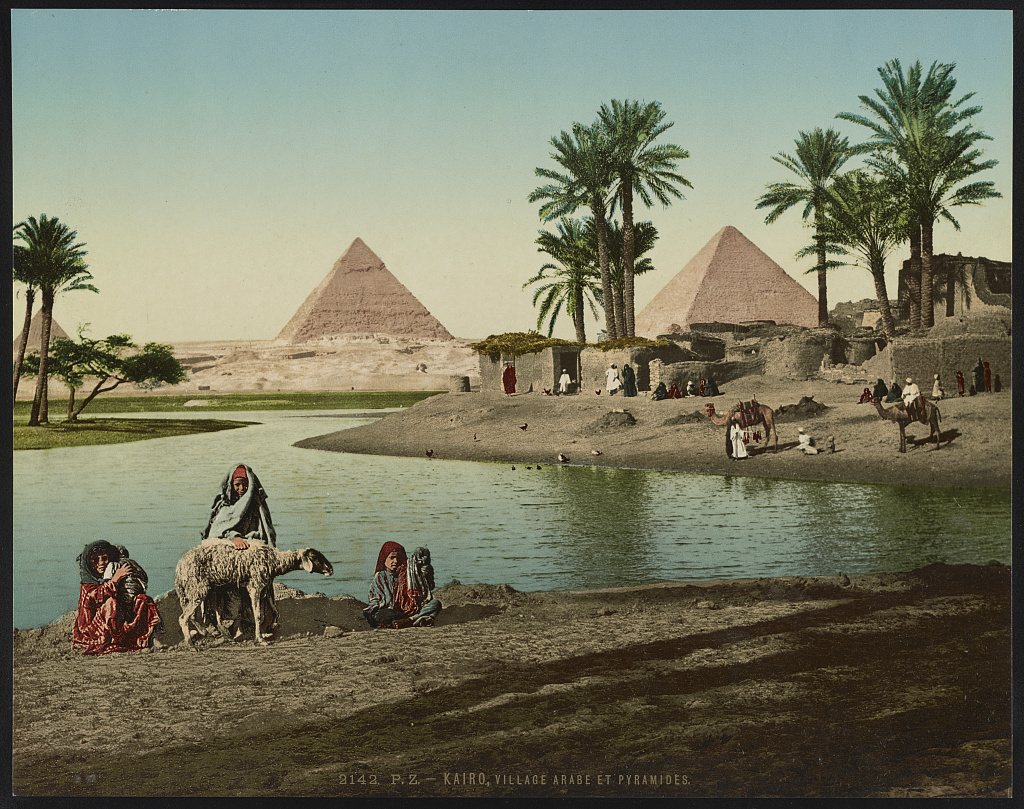

What embraces this archaeological landmark in Egypt?

560 kilometers northwest of Cairo

Siwa Oasis is home to one of the most important monuments dating back to the 26th Dynasty.

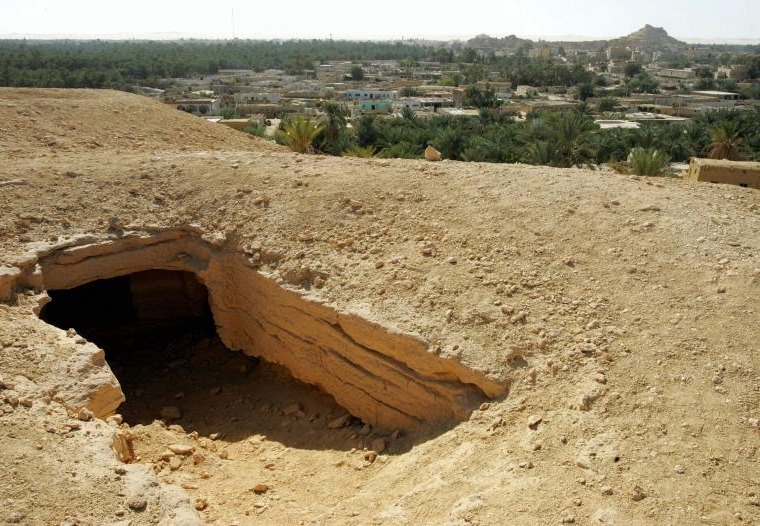

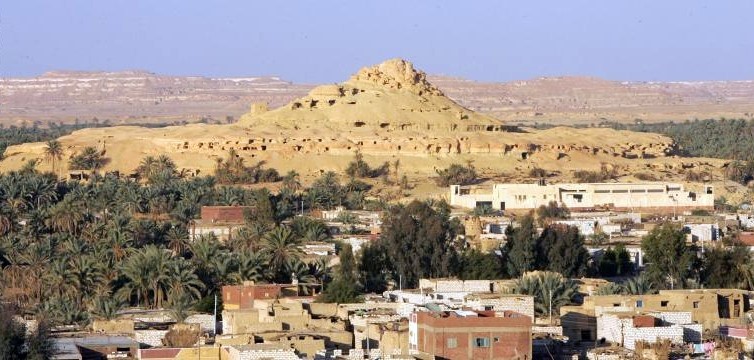

The conical mountain of the dead contains thousands of tombs carved into the rock

Where its inscriptions helped to date the most ancient tombs in it. Burial continued in this cemetery, that is, tombs, until the late Roman era and in relation to the most important graves contained in the mountain

It is the tomb of “Ba Thot”

And the tomb of “Miso Isis”

And the cemetery “Crocodile”

In addition to the tomb of “Sea Amon”

Which is the most beautiful in Western Sahara that the tomb of “Sea Amon” in fact

“The ancient Egyptian doctrine is translated into resurrection and eternity.” Not only that, but the walls of the tomb reflect a clear fusion between Egyptian and Greek arts. This landmark is characterized by being one of the wonders of the Siwa Oasis, which has always been distinguished by its various myths and stories.

It is noteworthy that the history of the discovery of the Mountain of the Dead dates back to 1944, specifically during the Second World War, where the Siwa people went to the mountain out of hiding, discovering the existence of the Pharaonic tombs that are located inside it.

The Mount of the Dead

The Mountain of the Dead is located 2 km from the Siwa region of Marsa Matrouh Governorate and was discovered by chance in 1944 during the Second World War when the people of Siwa took refuge in the mountain and discovered the tombs in it which is a conical shape with a height of 50 meters and consists of limestone soil and is considered an archaeological cemetery This mountain is distinguished by its amazing view, from below to above, it is tombs of the dead carved in the form of a beehive of stone in the form of regular and consecutive rows in a geometric shape similar to the shape of the ancient oasis. The history of this ancient cemetery dates back to the 26th Dynasty and extends to the Ptolemaic and Roman era. These tombs combine in their design between ancient Egyptian art and Greek art. This merger arose as a result of mixing cultures. Some of these tombs are found at great depth and each cemetery is a rectangular vestibule that ends into a wide square courtyard and this courtyard is branched from a group of holes dedicated to the status of the dead. The most beautiful tombs present are the cemetery of Si Amoun, which belongs to the ancient Greeks, who used to follow the ancient Egyptian religion. He lived in Siwa and was buried there according to that religion. This cemetery was well preserved. This cemetery has a group of prominent reliefs and includes a drawing representing the goddess Nat and it is standing under the sycamore tree. Then another cemetery called the cemetery cemetery and named by this name in relation to the inscriptions engraved on it which is a yellow crocodile shape representing the Subic god and this cemetery is a structure similar to a component cave Of three rooms and the owner of this cemetery has not been identified yet. Another cemetery is called Thebre Pathot, which is decorated with charming drawings and engravings dyed in red, which are dominated by pottery used in Siwa until now, and there is a stone sarcophagus placed on the floor of the burial chamber. In its entirety, many, many landmarks and treasures of the Sahara Desert.

Block Statue of Senwosret-senebnefny

Block Statue of Senwosret-senebnefny.

Egypt,

Middle Kingdom,

late Dynasty 12,

circa 1836-1759 B.C.E.

Quartzite

2674 x 165/16 x 181/8 in

(68.3 x 41.5 x 46 cm).

Block statues show their subjects

—almost always male—seated on the ground with their knees drawn to their chests; a cloak usually envelops the limbs and torso. The resulting block-like form gives these statues their name.

Block statues first appeared in the Twelfth Dynasty, nearly one thousand years after most statue types had been developed. Some Egyptologists suggest that the invention of such a distinctive sculptural form probably reflected the emergence of new religious ideas. The Twelfth Dynasty witnessed an increase in the belief that a non-royal person’s spirit could be reborn after death. Some scholars have suggested that the block statue represents the spirit as it emerges from a mound in the underworld at the glorious moment of rebirth.

Others see it as a demonstration of the intensification of personal piety that occurred during the period. Most early block statues were found in temples. Because the squatting pose in Egyptian art conveys submission, block statues are thought to depict men observing temple priests as they perform rituals for the gods, like obedient members of an eternal audience.

Head from a Female Sphinx

Head from a Female Sphinx.

Found in Italy,

said to have been in the ruins of Emperor Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli,

outside Rome; originally from Egypt, probably Heliopolis. Middle Kingdom,

Dynasty 12,

reign of Amunemhat II,

circa 1876–1842 B.C.E. Chlorite

155⁄16 x 131⁄8 x 1315⁄16 in.

(38.9 × 33.3 × 35.4 cm).

Small details sometimes provide crucial clues to understanding a sculpture. On this object, for example, the back of the wig extends horizontally instead of downward, indicating that the head originally belonged to a sphinx, a mythological creature with a human head and a lion’s body. Sphinxes represented the king’s ability to crush Egypt’s enemies. Although sphinxes were usually male, the heavy striated wig shown here only appears on representations of women.

This statue’s inlaid eyes, probably of metal and colored stones, were pried out in antiquity, resulting in extensive damage. Repairs to the eyes, lips, and chin were apparently made in the eighteenth century.

Female Figurine

Female Figurine.

Egypt

from Ma’mariya.

Predynastic Period

Naqada II

circa 3500–3400 B.C.E.

Terracotta, painted,

111⁄2 x 51⁄2 x 21⁄4 in.

(29.2 × 14 × 5.7 cm).

Based on images painted on jars of the same date, the female figure with upraised arms appears to be celebrating a ritual. The bird-like face probably represents her nose, the source of the breath of life. The dark patch on her head represents hair, also a human trait. Her white skirt indicates a high-status individual.

Statue of Nykara and His Family

Statue of Nykara and His Family.

Egypt

Old Kingdom

late Dynasty 5

circa 2455–2350 B.C.E

Limestone, painted

225⁄8 x 141⁄2 x 107⁄8 in

(57.5 × 36.8 × 27.7 cm)

This family statue depicts Nykara, whose title is Scribe of the Granary, seated between the two standing figures of his wife and son. If Nykara were shown standing, his dimensions are such that he would tower over the other two figures. Also, although the boy’s nakedness, sidelock of hair, and finger-to-mouth gesture indicate that he is very young, he is depicted as the same height as his mother. These disproportions apparently resulted from the sculptor’s desire to show all three heads in a row.

Kneeling Statue of Senenmut

Kneeling Statue of Senenmut

Egypt

from Armant.

New Kingdom

Dynasty 18

joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III

1478–1458 B.C.E

Granite

189⁄16 x 67⁄8 in

(47.2 × 17.4 cm)

base: 63⁄4 x 215⁄16 x 119⁄16 in

(17.2 × 7.5 × 29.3 cm)

Occasionally an innovative artist enhanced a traditional sculptural form. This statue of Senenmut—an important official during the joint reign of Queen Hatshepsut and King Thutmose III—appears in the classic kneeling pose known since the Fourth Dynasty (circa 2625–2500 B.C.E.). Old and Middle Kingdom kneeling statues show a subject with his hands resting on his thighs or holding a pair of tiny round vessels. The sculptor of this piece, however, depicted Senenmut presenting a complex object: a cobra resting in a pair of upraised arms, wearing cow horns with a sun-disk. Egyptologists interpret this image as a cryptogram of Hatshepsut’s throne name (Ma`at-ka-re).

The sculptural form of a kneeling man holding an intricate symbolic image first appeared in statues of Senenmut and continued for hundreds of years. Perhaps this new type of statue was the product of Senenmut’s imagination, as interpreted by a skilled and receptive artist.

Head of an Egyptian Official

Head of an Egyptian Official

Egypt

reportedly from Memphis.

Ptolemaic Period,

circa 50 B.C.E.

Diorite,

165⁄8 in. (42.2 cm).

The rich, dark patina of this head is not ancient; the original surface has a duller tone. Whether the head represents an individual is a matter of dispute. It may depict a particular but now unknown priest or government official, or it may be a stylization. The curly locks reflect Hellenistic influence, an important component of Egyptian art of the ptolemaic Period, but the formulaic execution is Egyptian. One scholarly opinion holds that the face consists of many nonintegrated features drawn from disparate sources and cannot therefore be individualizing. According to this theory, the front and side views do not merge and the forehead is a schematic, unrealistic trapezoidal configuration. Likewise the facial planes are allegedly too sharply demarcated and the heavily lidded eyes are oversized hieroglyphs. The accuracy of these claims is open to question.

Cartonnage of Nespanetjerenpere

Cartonnage of

Nespanetjerenpere

Egypt

probably from Thebes

Third Intermediate Period

Dynasty 22 to early Dynasty 25

circa 945–718 B.C.E.

Linen or papyrus mixed with plaster

pigment, glass, lapis lazuli

height: 6911⁄16 in. (177 cm).

The decoration of Nespanetjerenpare’s cartonnage

richly details the theme of resurrection and permanence. Above the wesekh-collar is a protective pectoral in the form of a djed-pillar and a tyet-amulet. The djed-pillar is the hieroglyphic writing of the word “stability” or “endurance,” and the sign tyet, often written in assocation with djed, expresses the idea of well-being. Below the wesekh-collar is a ram-headed falcon pendant, a representation of the solar god as he travels through the underworld at night. Ihe cartonnage base is decorated with ankh-signs and was-scepters, the hieroglyphs for “life” and “power.” The small registers in the front depict a variety of deities associated with the parts of the body—like the eyes, lips, and teeth—deities who serve to protect the owner and keep his mummy bound together for eternity

The Wilbour Plaque

The Wilbour Plaque

Egypt

probably from Akhetaten

(“Horizon of the Aten”)

modern Amarna

New Kingdom

Dynasty 18

reign of Akhenaten

probably late in his reign

circa 1352–1336 B.C.E.

Limestone

63⁄16 x 811⁄16 x 15⁄8 in.

(15.7 × 22.1 × 4.1 cm)

One of the world’s best-known works of Amarna art, the Wilbour Plaque is named for the American Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour (1833–1896),

who purchased it in 1881. The plaque was never part of a larger scene. Originally, it was suspended on a wall by a cord inserted through the hole at the top.

Artists used it as a model for carving official images of an Amarna king and queen.

The queen shown here is certainly Nefertiti; the king may be Akhenaten

hi co-regent Smenkhkare, or young Tutankhaten

(later Tutankhamun).