ابراج الفراعنة

01 / 12

برج “سيت

رمز الطاقة والطموح

مواليد:

28 مايو إلى 18 يونيو

ومن 28 سبتمبر إلى 2 أكتوبر

متسامح وشجاع، ويبحث عن الجودة في كل شيء.

متعدد المواهب ومتحمس دائمًا، ويرغب في الفوز.

يركز على حاضره ويتعلم من ماضيه.

يجذبه التحدي والتغلب على المصاعب،

ويحقق انتصارات بسبب صفاته.

لا يتقن الاستفادة مما يحققه،

وقد يتركه بعد مجهود كبير يذهب بلا فائدة

=========

02 / 12

برج “آمون رع

رمز الخلق

مواليد:

8 إلى 21 يناير

ومن 1 إلى 11 فبراير

شخص جذاب ومؤثر في الآخرين.

يحب الآخرين ويساعدهم،

ويستطيع حل المشكلات بمهارة وتقييم عواقب المواقف الصعبة،

ويتمهل في اتخاذ القرارات. تفكيره واضح،

ويميل لإخفاء أفكاره ورؤيته عن الآخرين.

يبالغ أحيانًا في توقع المثالية في كل شيء

ويرغب في السيطرة على الآخرين أحيانًا

03 / 12

برج “حابي

رمز النيل”

مواليد:

1 إلى 7 يناير

ومن 19 إلى 28 يونيو

ومن 1 إلى 7 سبتمبر

ومن 18 إلى 28 نوفمبر

شخص يحب الاستمتاع بالحياة الرغدة الطيبة

مبتكر، وجاذب للانتباه، وخفيف الظل.

هو محامي جيد عن الأفكار التي يؤمن بها،

ويستطيع التمييز بين النافع وغير النافع.

يبتعد عن الصراعات ويتحاشاها،

ويخاف الخيانة والغدر،

ويستطيع التفرقة بين من يحبه ومن لا يحبه

04 / 12

برج “أوزوريس

رمز المعرفة”

من 1 إلى 10 مارس

ومن 27 نوفمبر إلى 18 ديسمبر

نشيط وشجاع وواضح،

يستطيع تخطي العقبات بتفكيره الإيجابي

يجب المعرفة والعلوم والفنون،

يحترم التخصص ويقدر مواهب الآخرين

وينجذب للأشياء الصعبة.

أحيانًا يخلق أعداء لنفسه بسبب غيرة الآخرين منه التي يتعمدها أحيانًا

ويصاب بالإحباط بسبب انجذابه في بعض الأوقات للأشياء المستحيلة

05 / 12

برج “إيزيس

رمز الوفاء”

مواليد:

11 إلى 31 مارس

و18 إلى 29 أكتوبر

و19 إلى 31 ديسمبر

ملهم ومحدد الهدف، خيالي بعض الشيء،

لكنه يؤمن بالحب. حسن المظهر ويجيد الدفاع عن نفسه

ولديه طبيعة كريمة وسخية مع الآخرين.

منفتح ويستطيع الانسجام مع الآخرين بسهولة

كما يحب التجديد وخوض التجارب الجديدة.

يتوقع أحيانًا الكثير من الآخرين مما يصيبه بالإحباط،

ولا يتسامح مع من يضلله،

ويميل أحيانًا للعزلة،

وقد يساء فهمه من الآخرين ويسبب له ذلك بعض المشاكل

06 / 12

برج “توت

رمز الزمن والبحث”

مواليد:

1 إلى 19 أبريل

و8 إلى 17 نوفمبر

اجتماعي، يحب المعارك وينجذب للبحث.

يدخل في سباق مع الآخرين طوال الوقت ويحب محاكاتهم

يحب التباهي والزهو، ويقلد من يعجب بهم،

ولا يستطيع فهم الآخرين أحيانًا.

عيوب شخصيته توقعه في مشكلات طوال الوقت،

ويرهق نفسه أحيانًا في طريق غير الذي تميز فيه

07 / 12

برج “سخمت

رمز الحب والطب والعقاب”

مواليد:

29 إلى 11 أغسطس

و30 أكتوبر إلى 7 نوفمبر

يقظ وحذر، لا يمنح ثقته بسهولة،

ولا يسامح من يخونه.

مستعد للدفاع عن نفسه ضد أي هجمة في أي ظرف

يشعر بقيمة نفسه، ويحبون تقدير الآخرين لهم.

يبحث عن المثالية ويظهرون أحيانًا في أعين الناس بمظهر الصلابة والتشدد

إذا عشق يفقد عقله، وكذلك إذا غضب

08 / 12

برج “حورس

رمز الحماية والنصر”

مواليد:

20 أبريل إلى 8 مايو

و12 إلى 19 أغسطس

كريم ومخلص ويحب الوضوح في كل شيء.

لماح ولديه ضمير يقظ، يعرف مسئولياته جيدًا،

ولديه روح محارب.

لا يتراجع ولا يحترم السلطة إن كانت في يد من لا يستحق.

عملي وواقعي، ويثق أحيانًا أكثر من اللازم في الآخرين

وهو مكشوف جدًا لأعداءه لذلك يقع في المشاكل

09 / 12

برج “باستيت

رمز الموسيقى والبيت”

مواليد:

14 إلى 28 يوليو

و23 إلى 27 سبتمبر

و3 إلى 17 أكتوبر

يحب الفنون والابتكار والجمال،

هو سريع البديهة ولديه قدرة على الإقناع

ويستطيع التكيف بسهولة مع المتغيرات.

يستخدم عقله لحل المشكلات ويوجه جهوده لفعل الخير.

لديه طبيعة حذرة وقلقة، ويتجنب المخاطر،

ويتردد أحيانًا ويتجنب المواجهات

10 / 12

برج “مووت

رمز الأمومة”

مواليد:

22 يناير إلى 31 يناير

و8 إلى 22 سبتمبر

لطيف وذكي ودقيق

محب للآخرين ولديه روح حماية وأمومة

ويشعر بالمسئولية تجاه الآخرين.

يفكر في وجود معنى لحياته،

ويعرف أين يستثمر مجهوده.

هو أيضًا قادر على تقديم تضحيات عظيمة

ويحب الأنشطة الاجتماعية.

تفاؤله غالبًا ما يعرضه لإحباطات كبيرة

كما تسبب حساسيتهم تجاه الخطأ

ورؤيته المثالية بعض الخلافات مع الآخرين

11 / 12

برج “جيب

رمز الأرض”

مواليد:

12 إلى 29 فبراير

و20 إلى 31 أغسطس

شخص يمكن الاعتماد عليه، واقعي، لديه قدرة على العطاء للآخرين.

يستطيع التفكير بشكل منطقي وتحقيق الإنجازات،

وتحويل أفكاره إلى أشياء ملموسة. مستقر، وهادئ،

ويعرف كيفية التخفيف عن الآخرين في معاناتهم وألمهم.

يحترم وعوده، ولا يتسامح مع من لا يحترمون وعودهم.

يميل لدفن معاناته الخاصة،

ويتسبب ذلك في شعوره بالقلق والوحدة أحيانًا

12 / 12

برج “أنوبيس

رمز التفكير والهدوء”

مواليد:

9 إلى 27 مايو

و29 إلى 13 يوليو

يحبون التفكير جيدًا ودراسة الموقف قبل اتخاذ القرار

يفضل مواليد هذا البرج الحياة الهادئة،

والعيش في سلام. مزاجي، ولديه طبيعة متقلبة أحيانًا،

ويحب العزلة. عاطفي ويحب إخفاء مشاعره خلف ابتسامة.

يتعلق بالماضي، وينجذب للأشياء الصعبة

إذا وقع في الحب ينكسر بسهولة،

وانعزاله عن الناس يدفعهم لسوء فهمه أحيانًا

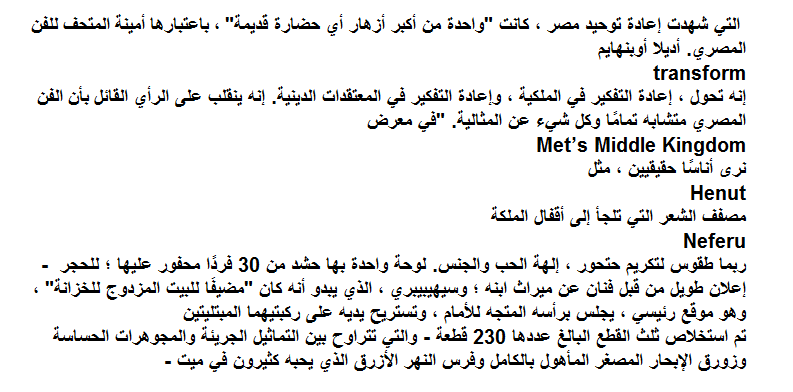

Phallus Worship And Ancient Religious Sex Customs

Phallocracy literally means “The power of the Phallus” it is the religious and cultural system symbolized the male reproductive organ in permanent erection. Literally this symbolized the dominance of men over women in the historic times. In the historic times the worship of male organ is in conjunction with worship of the female counterpart. The cultures that respect sexuality normally dominated by men and hence their rituals present phallus as icon. In terms of sex Phallocracy disregard of sexual satisfaction of females. This is simply mean worship of generative powers.

Phallus Worship in India

The prehistoric people celebrated great festivals not only in their honor but also as a license for their gaiety. In the festivals they carried the image of phallus openly. A giant phallus was carried in parade and the stunt followers sung obscene songs very loudly in open throat. At the end of the procession the head priest garland the head of the phallus. The festival mood extends till the night and the people indulged without a feel embarrassed in the most infamous vices. . Most of the phallic festivals were celebrated during the harvest seasons. In Rome the great festival of Venus was celebrated in April, and a giant phallus was taken in car procession. The procession was led by the ladies to the temple of Venus. At the temple the sexual parts of the goddess were presented to them.

The same practice was followed by the Teutonic peoples also. They celebrated the festivals during the summer months. All these festivals accompanied with the phallic worship, which is similar to that of the Roman festivals. In France in and around La Rochelle, small phallus shaped small cakes are made as offerings at Easter.

In the town of Saintes,

the Palm Sunday

was called in the name fete des pinnes

(pinne is a popular vulgar word).

The children carry phallus shaped bread and palm branches. At the end of the procession the priest blessed the cakes and the women preserved them as an amulet for the consecutive year. Similarly at St. Jean-de’Angely, same practice was followed but the cake name was fateux. It is common in The Romans customs to make cakes in the form of male and female genital parts.

Even in India people worship combination of male and female genital organs as Lingam still today.

Pyramids at Giza

Pyramids at Giza

How the Pyramids at Giza were built is one of Egypt’s biggest mysteries.

The Giza Pyramids, built to endure an eternity, have done just that. The monumental tombs are relics of Egypt’s Old Kingdom era and were constructed some 4,500 years ago.

Egypt’s pharaohs expected to become gods in the afterlife. To prepare for the next world they erected temples to the gods and massive pyramid tombs for themselves—filled with all the things each ruler would need to guide and sustain himself in the next world.

Pharaoh Khufu began the first Giza pyramid project, circa 2550 B.C. His Great Pyramid is the largest in Giza and towers some 481 feet (147 meters) above the plateau. Its estimated 2.3 million stone blocks each weigh an average of 2.5 to 15 tons.

Khufu’s son, Pharaoh Khafre, built the second pyramid at Giza, circa 2520 B.C. His necropolis also included the Sphinx, a mysterious limestone monument with the body of a lion and a pharaoh’s head. The Sphinx may stand sentinel for the pharaoh’s entire tomb complex.

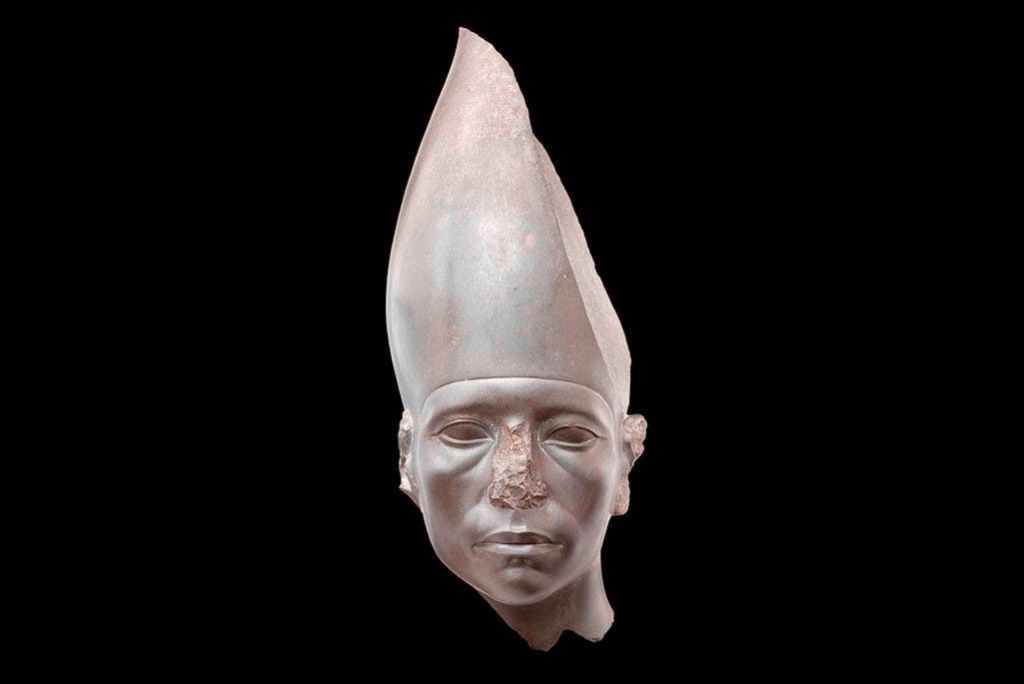

The third of the Giza Pyramids is considerably smaller than the first two. Built by Pharaoh Menkaure circa 2490 B.C., it featured a much more complex mortuary temple.

Each massive pyramid is but one part of a larger complex, including a palace, temples, solar boat pits, and other features.

Building Boom

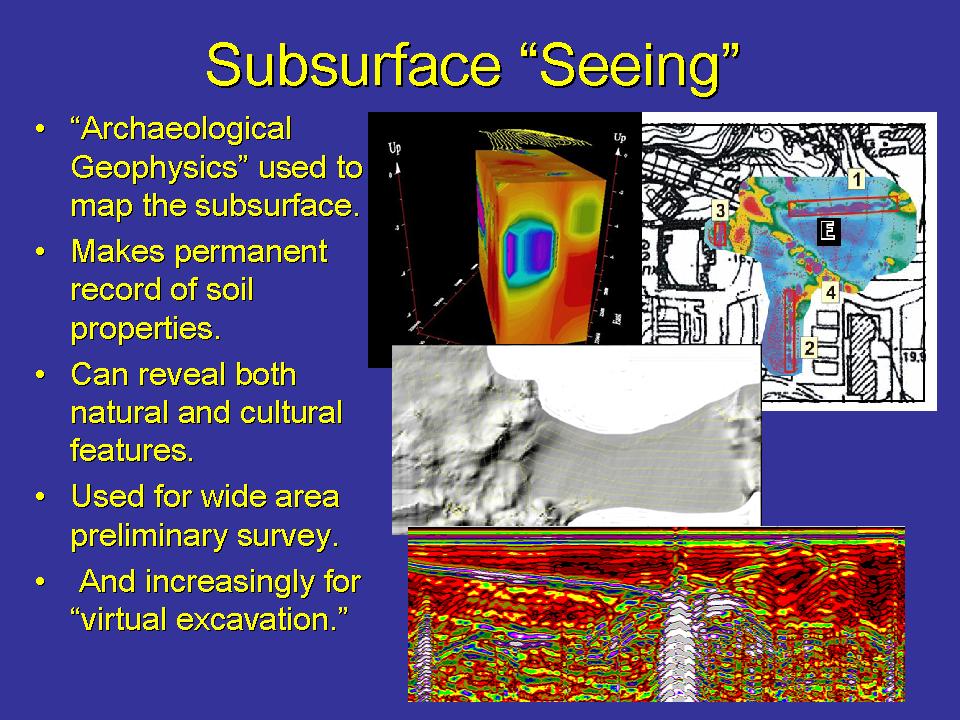

The ancient engineering feats at Giza were so impressive that even today scientists can’t be sure how the pyramids were built. Yet they have learned much about the people who built them and the political power necessary to make it happen.

The builders were skilled, well-fed Egyptian workers who lived in a nearby temporary city. Archaeological digs on the fascinating site have revealed a highly organized community, rich with resources, that must have been backed by strong central authority.

It’s likely that communities across Egypt contributed workers, as well as food and other essentials, for what became in some ways a national project to display the wealth and control of the ancient pharaohs.

Such revelations have led Zahi Hawass, secretary general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities and a National Geographic explorer-in-residence, to note that in one sense it was the Pyramids that built Egypt—rather than the other way around.

Preserving the Past

If the Pyramids helped to build ancient Egypt, they also preserved it. Giza allows us to explore a long-vanished world.

“Many people think of the site as just a cemetery in the modern sense, but it’s a lot more than that,” says Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Tufts University Egyptologist Peter Der Manuelian. “In these decorated tombs you have wonderful scenes of every aspect of life in ancient Egypt—so it’s not just about how Egyptians died but how they lived.”

Tomb art includes depictions of ancient farmers working their fields and tending livestock, fishing and fowling, carpentry, costumes, religious rituals, and burial practices.

Inscriptions and texts also allow research into Egyptian grammar and language. “Almost any subject you want to study about Pharaonic civilization is available on the tomb walls at Giza,” Der Manuelian says.

To help make these precious resources accessible to all, Der Manuelian heads the Giza Archives Project, an enormous collection of Giza photographs, plans, drawings, manuscripts, object records, and expedition diaries that enables virtual visits to the plateau.

Older records preserve paintings or inscriptions that have since faded away, capture artifacts that have been lost or destroyed, and unlock tombs not accessible to the public.

Armed with the output of the longest-running excavations ever at Giza, the Harvard-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Expedition (1902-47), Der Manuelian hopes to add international content and grow the archive into the world’s central online repository for Giza-related material.

But he stresses that nothing could ever replicate, or replace, the experience of a personal visit to Giza.

Egypt’s pharaohs welcomed summer with this fabulous festival

Every year ancient Egyptians eagerly anticipated the coming of Akhet

the flooding season.

Meaning “inundation,”

Akhet was the all-important time when the Nile’s floodwaters replenished the land and restored Egypt’s fertility. This time of joyous renewal was also when ancient Egypt held one of its most spectacular and most mysterious festivals:

the Feast of Opet.

Opet was celebrated in the city of Thebes, and the centerpiece of the festival was a grand procession from Karnak to Luxor. In these processions, statues of the city’s most sacred gods—Amun-Re, supreme god, his wife, Mut, and his son, Khons—were placed in special vessels called barks and were then borne from one temple to the other.

Opet’s formal name is heb nefer en Ipet, which translates to “beautiful feast of Opet.” The word opet or ipet is believed to have referred to the inner sanctuary of the Temple of Luxor. So important was this festive event that the second month of Akhet, when the feast typically occurred, was named after it: pa-en-ipet, the [month] of Opet. During the reign of Thutmose III (1458-1426 B.C.), the festival lasted for 11 days. By the start of the rule of Ramses III in 1187 B.C., it had expanded to 24 days; by his death in 1156 B.C., it had stretched to 27.

A new kingdom rises

The beautiful feast became a major celebration in the early New Kingdom (ca 1539-1075 B.C.)

when the 18th dynasty came to power, after driving out the Hyksos invaders who had occupied the northern part of the Nile Valley for 200 years. Egypt’s new rulers wasted no time in making its capital city Thebes a vast ceremonial stage to celebrate the consolidation of power, and the Opet festival took center stage.

Egypt displayed its greatness with impressive feats of engineering in the expansion of its two great temple complexes at Karnak and Luxor on the eastern bank of the Nile. One of the early pharaohs of the 18th dynasty, Thutmose I expanded the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak. His successors continued improvements to the temple’s ceremonial spaces, constructing processional avenues, courts, and pylons. Karnak grew to become one of the largest religious complexes, measuring nearly two square miles.

Famous for its soaring columns and statues of Ramses II, the impressive Luxor Temple was built between and during the reigns of Amenhotep III and Ramses II, circa 1400 to 1200 B.C. Archaeologists believe a smaller temple stood there originally before Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun, and Ramses II enlarged the complex and added a large court, numerous halls, a majestic colonnade, a pylon, and obelisks.

The processional route between the temples varied with time, sometimes traveling by foot along the Avenue of Sphinxes, a road nearly two miles long and lined with statues of the mythical beasts. At other times, the sacred statue traveled from Karnak to Luxor in a specially made bark, known in Egyptian as the Userhat-Amun (“mighty of prow is Amun”). This vessel was built of Lebanon cedar covered with gold. Its prow and stern were decorated with a ram’s head, sacred to the god

Evidence in pictures

Most of what is known about the festival is iconographic and comes from artwork found at the temple precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak, the Temple of Luxor; and the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu.

The earliest evidence comes from the Red Chapel of Queen Hatshepsut (reigned 1479-1458 B.C.).

During her reign, only Amun-Re traveled from Karnak to Luxor. The reliefs from the Red Chapel depict the god’s shrine being carried by priests. Initially, the journey was made on foot, stopping at six altars constructed by Hatshepsut along the Avenue of Sphinxes that ran between the two temples. The reliefs then show both statue and the priests returning downstream to Karnak by boat.

The Luxor reliefs show the evolution of the celebration and how it changed over time. The colonnade, added during the time of Tutankhamun’s reign, has impressively detailed reliefs that give insights into Opet rituals and how they changed from the time of Hatshepsut. The artworks reveal that Amun-Re has been joined by his consort, Mut, and their son, Khons, in the procession. Some reliefs even show the ruling pharaoh as part of the group.

Changes in the route can be seen in the artwork at Luxor. The statues of the gods traveled in both directions along the Nile rather than along the Avenue of Sphinxes. During the outward trip south, against the flow of the river, the bark was pulled by other boats and by people on the riverbanks. High-ranking officials who took part regarded rowing the boats as a great honor worthy of being recorded in their life stories. During the journeys along the river, the barks were escorted from the shore by soldiers, dancers, and bearers of offerings, among them fattened oxen that were to be sacrificed.

The reliefs make a great effort to depict the grand spectacle: Many priests support the barks and statues, while a crowd makes a joyous din with sistrum rattles. The gods’ barks were brought alongside the jetty at the Temple of Luxor and were carried on the shoulders of the priests to the sacred precinct. A series of ceremonies were conducted in the outer courts, after which the barks were taken into the inner sanctuary, accompanied solely by high-ranking priests and the pharaoh. Once the ceremonies were completed, the barks returned downstream to Karnak.

Mysteries of Opet

Even though the surviving reliefs provide considerable information about the processions, they offer no indication of the exact purpose of the rituals performed at Luxor. Despite the conspicuousness and majesty of Opet in art- works, no text describing the event survives. Neither have traces of a processional bark from the festival ever been found.

One popular theory is that the Opet rites confirmed the monarch’s possession of the royal ka. This life force inhabited the bodies of all legitimate pharaohs of Egypt and passed from the old to the new on the latter’s death. An annual confirmation of such a process would help bolster the king’s authority.

A popular feast

If the noisy, festive aspect of Opet provided a contrast to the priestly rituals, the festival’s emphasis on food was also appreciated by the populace. Reliefs at both Karnak and Luxor temples show the details of Opet feasting. On one panel at the Temple of Luxor, Amenhotep III is depicted presenting the bounty for the festival: Bread, fruit, honey, game, and other delicacies are depicted in abundance.

Opet’s fusion of majesty and popular merry-making helped forge a powerful bond between the people and their pharaoh during the New Kingdom. Centuries later, after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 B.C., the conqueror’s agents in Thebes observed how the festival’s symbolic power could be adapted to confer divine legitimacy upon Alexander’s control of the region. Alexander built his own chapel in the Temple of Luxor and decorated the walls with his likeness in the presence of Amun-Re.

Opet celebrations are believed to have continued until Roman times. The feast and its divine parade finally fell out of favor after the rise of Christianity in Egypt when the old gods and the old ways were cast aside

The Alien god belonging to the house of Osiris Medjed

The Alien god belonging to the house of Osiris Medjed

the one very peculiar god:

Medjed.

WE ARE MEDJED

the mythology of Medjed, ,

it says:

“(…) Do not speak of your false justice.

We do not need the spread of such falsehood.

We are the true executors of justice. (…)

If you reject our offer,

the hammer of justice will find you.

We are Medjed.

We are unseen.

We will eliminate evil.”

he is a very minor god.

let us learn a little bit about this god.

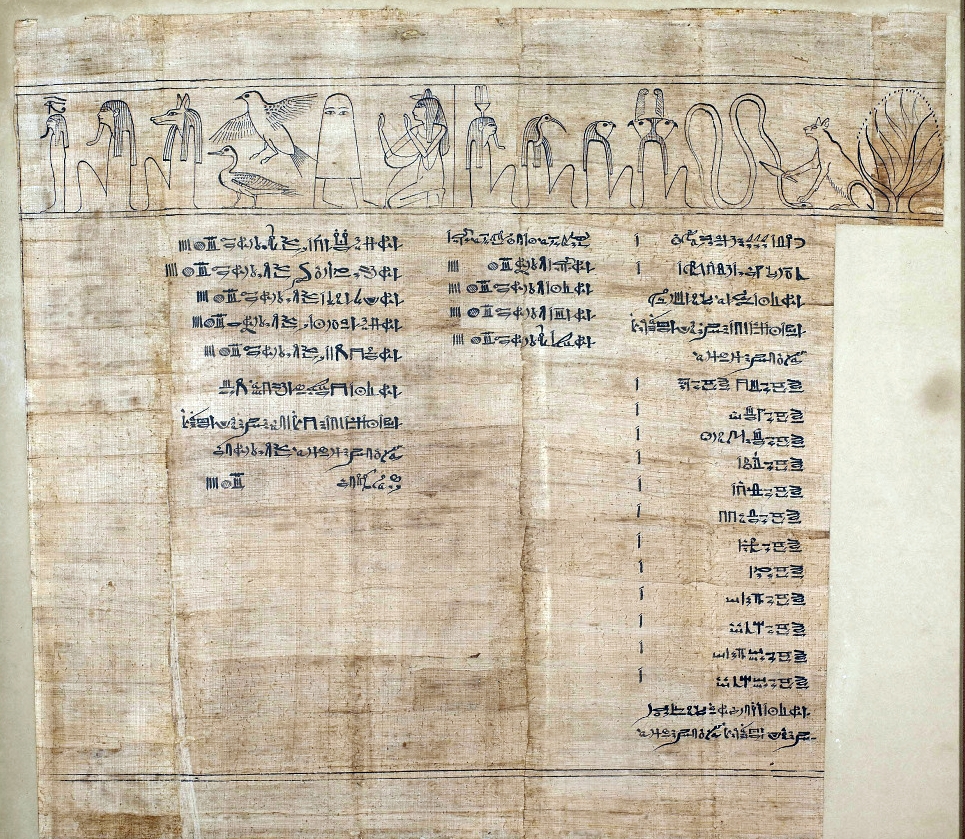

The main source of knowledge on

Medjed

is the so-called

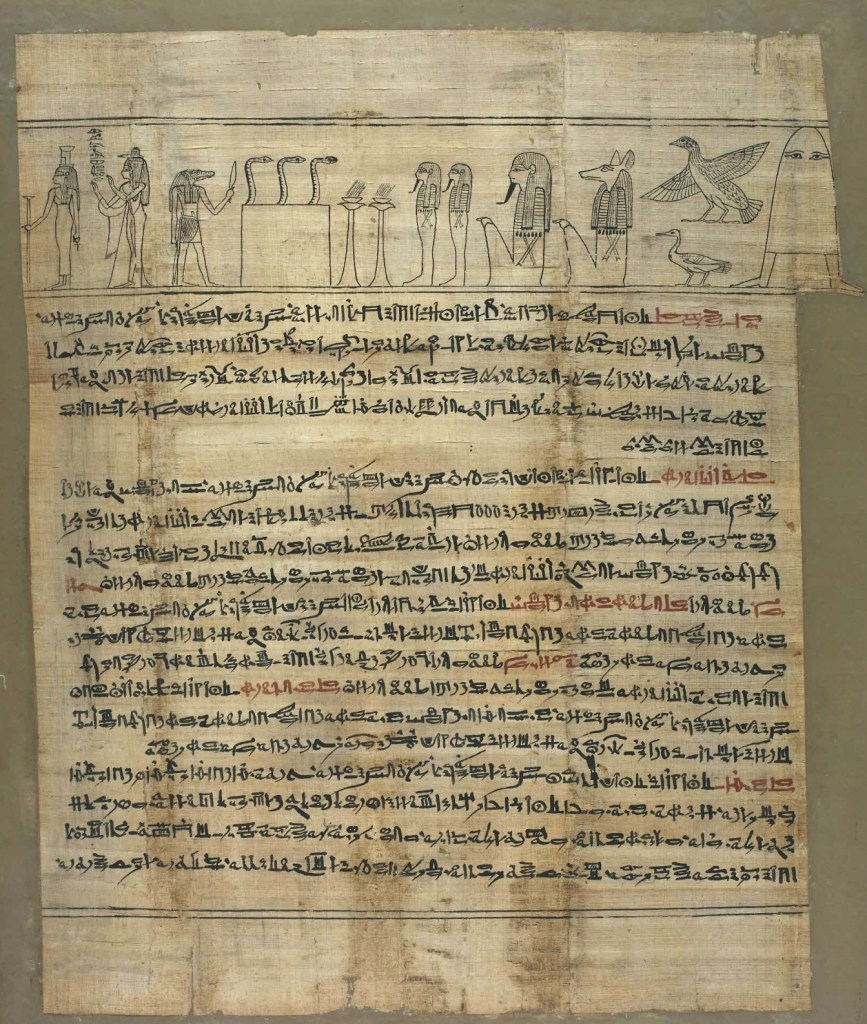

Greenfield Papyrus

where he appears twice.

If the name of the papyrus seems a little awkward,

that is because it is common for ancient Egyptian artifacts (especially papyri) to be named after the collector who owned it during the heyday of Egyptomania.

In this case, this particular papyrus belonged to Mrs. Edith M. Greenfield,

who donated it to the British Museum in 1910.

The curator’s comments on the online collection of the British Museum summarizes it nicely:

The ‘Greenfield Papyrus

is one of the longest and most beautifully illustrated manuscripts of the ‘Book of the Dead’ to have survived. Originally, over thirty-seven metres in length, it is now cut into ninety-six separate sheets mounted between glass. It was made for a woman named Nestanebisheru, the daughter of the high priest of Amun Pinedjem II. As a member of the ruling elite at Thebes, she was provided with funerary equipment of very high quality. Many of the spells included on her papyrus are illustrated with small vignettes, and besides these there are several large illustrations depicting important scenes.”

―British Museum (2017)

The Greenfield Papyrus dates from the historical period known as New Kingdom, possibly from the end of the 21st Dynasty or the beginning of the 22nd, around 950–930 BCE

(British Museum, 2017).

The vignettes mentioned in the description above appear on top of each sheet in a manner resembling — a comic strip

Majeed was mentioned in the papyrus

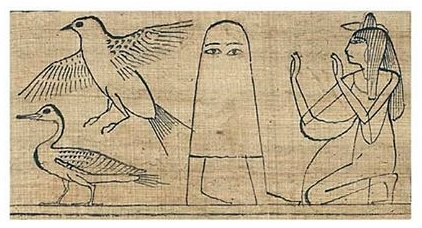

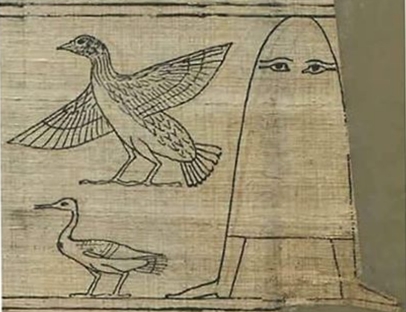

Figures 2 and 3.

So let’s take a closer look at it:

It is a shrouded form

Like ghost animation

(Figs 4 and 5),

But sometimes it is described as

Hill with eyes and feet

(British Museum, 2017).Because of its peculiar appearance, it is impossible to miss and / or ignore it even for the least aware.Close-up of Sheet 12 of Greenfield Papyrus

Text on papyrus

He calls it glorious

(Sometimes written as “michit” in ancient literature)

He says he “shoots from his eyes

But he himself is not visible

And that it “turns in the sky within a flame that results from its mouth.”

While its special form is not visible. “

This translation is according to Budge (1912);

This was the only translation of Greenfield’s papyrus

That I was able to reach. Regardless ,

Much agree with subsequent research on Majeed.

The above section is part

Chapter 17 (or spelling 17)

From the Book of the Dead.

Another place to look for glorious

It is the same spelling of 17 other versions of the Book of the Dead

(It varies, as I will explain later).

As expected, we can find references to Majeed

In the New Kingdom papyri (and later releases),

Including a group of well-known papyri

In the name of “The Good Recitation of the Book of the Dead”.

17 of these papyrus mantra are similar to Greenfield Papyrus

But bear some differences.

According to Budge (1898):

“I know that I walked [glorious] who is among them in the house of Osiris, shining light rays from his eye, but who is himself invisible. It revolves around the paradise stolen by the flame of his mouth, and he commands Habi [the god of the annual flood of the Nile],

But himself remains invisible. “

A new translation of this passage is provided by Faulkner et al. (2008) and Goelet et al. (2015):

“I know the name of this smartest among them who belongs to the house of Osiris, who shoots with his eyes, but he is not visible. The sky is surrounded by a fiery explosion in his mouth and Happy issues a report, but it is not visible.” Glorious his name here is “the smartest”,

Or his name may be translated to “smarter.”

This translation explains Majid, and turns it into “smartest” only:

Nearly all deities (and humans) were vulnerable to hitting enemies.

To summarize all the above information

Glorious invisible

(Hidden or invisible)

Can fly,

It can fire light rays from his eyes,

Can breathe fire

It can strike other objects.

Beside that

Nothing else is known about this deity.

Anywhere else

Lists Majeed (or) Mashit

In a chapter on

“Various deities”,

But whether this refers to the same deity

Lists

The gods who protect Osiris during 12 hours of the day and 12 hours of the night; one of them is glorious.

Majeed watches Osiris during the first hour of the day and twelve o’clock at night. This is in line with the passage

In spelling 17

It is said that Majid belongs to the house of Osiris

THE BOOK OF THE DEAD

Now let us make a brief pause to talk a little about the Book of the Dead.

The most important questions to address are:

(1) What is it?

(2) How it came to be?

(3) Is it a single book or is there more than one?

The Book of the Dead is a collection of funerary texts; its use was widespread and lasted for over one and a half millennium .

The Egyptians called it

the “Book of Coming Forth by Day”,

but “Book of the Dead”

was more appealing to the modern audience.

The book contained hymns praising the gods and several magical spells

to protect and guide the deceased through the perilous journey through

the Duat, which is the Egyptian underworld

The journey to a nice afterlife was riddled with dangers, fiends and tests, and the deceased needed all the help he/she could get.

The Book of the Dead was not a new invention, however. On the contrary, it has a long history, as it is derived from older writings. During the Old Kingdom, starting in the 5th Dynasty, funerary texts were written on the walls of the burial chambers inside the pharaoh’s

(and later also the queen’s) pyramid

These texts, written in hieroglyphic script, are called “Pyramid Texts” — a rather uninventive name, maybe, but efficient nonetheless. They were meant to help the deceased king to reach his rightful place among the gods in the afterlife. Later on, the right to an afterlife ceased to be a royal privilege and first the elite and then everyone was granted access to it

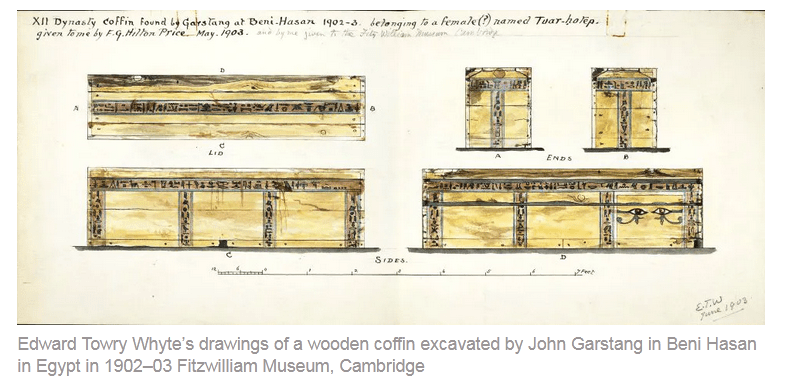

During the Middle Kingdom, the spells started to be written on the inner side of the coffins

(sometimes also on walls and papyri).

They are called, as you may have already guessed, “Coffin Texts”. Many new spells were added to the repertoire and they were, for the first time, illustrated. Afterwards, new spells were developed and everything started to be written on papyrus; the Book of the Dead thus came into being. The spells could be written either in hieroglyphic script or in hieratic

(a cursive form of the hieroglyphs)

and were usually richly illustrated.

The oldest known Book of the Dead is from Thebes (around 1700 BCE)

during the Second Intermediate Period, and by the New Kingdom, the Book had already become very popular

The most important thing to understand is that there is not a canonical Book of the Dead: when a person commissioned his/her own copy of the Book, they could choose the spells they wanted. Also, there are some differences among books even for the same spells, which can be due to poor copyediting, deliberate omission of parts of the spell or simple evolution through time.

To the modern public, the best-known scene from the Book of the Dead is the Judgement, or the “weighing of the heart” (Fig. 6).

This was the most critical step of the journey to the afterlife.

The heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Maat, the goddess of truth, balance and order. If the person behaved in life in accordance with the principles of Maat, he/she would be granted access to the afterlife.

Otherwise, his/her heart would be devoured by Ammit, a goddess whose body was a mix of crocodile, hippopotamus and lioness.

This so-called “second death”was permanent and thus much feared by the Egyptians.

Spell

for being transformed into a phoenix

I have flown up like the primeval ones,

I have become Khepri,

I have grown as a plant,

I have clad myself as a tortoise,

I am the essence of every god,

I am the seventh of those seven uraei who came into being in the West,

Horus who makes brightness with his person, that god who was against Seth,

Thoth who was among you in that judgement of Him who presides over Letopolis together with the souls of Heliopolis

the flood which was between them.

I have come on the day when I appear in glory with the strides of the gods

for I am Khons who subdued the lords.

As for him who knows this pure spell

it means going out into the day after death and being transformed at will

being in the suite of Wennefer

being content with the food of Osiris

having invocation-offerings, seeing the sun

it means being hale on earth with Re and being vindicated with Osiris

and nothing evil shall have power over him

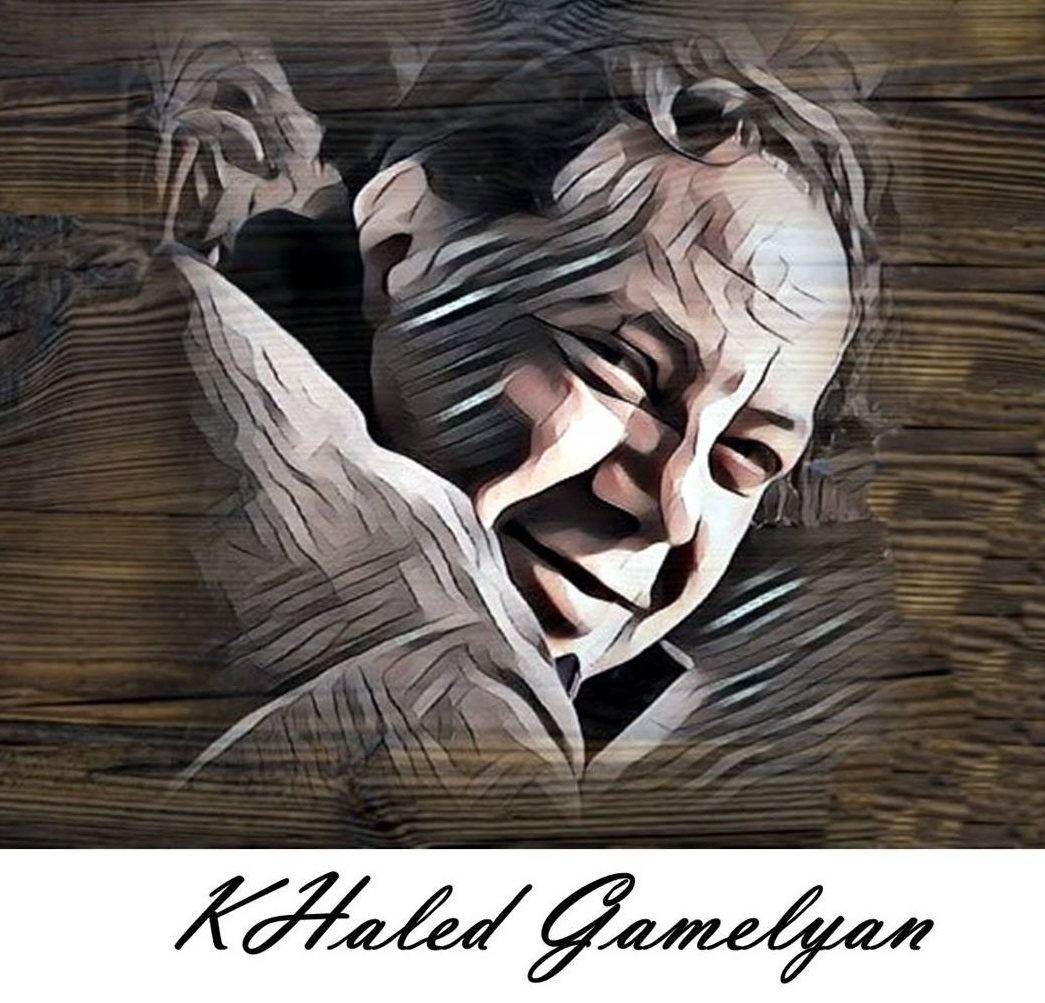

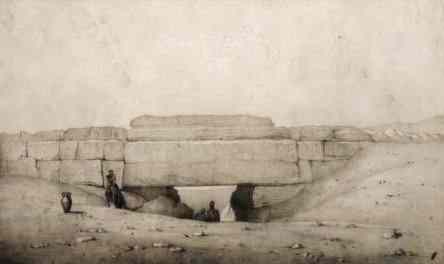

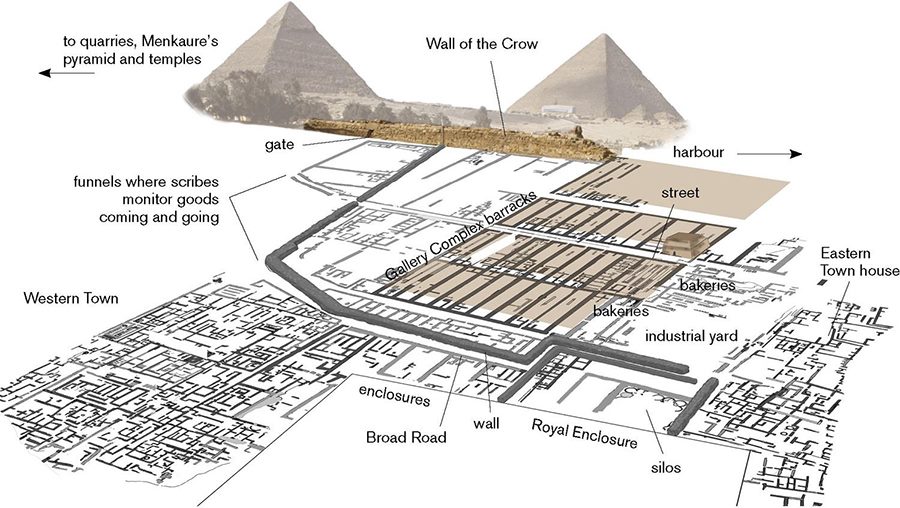

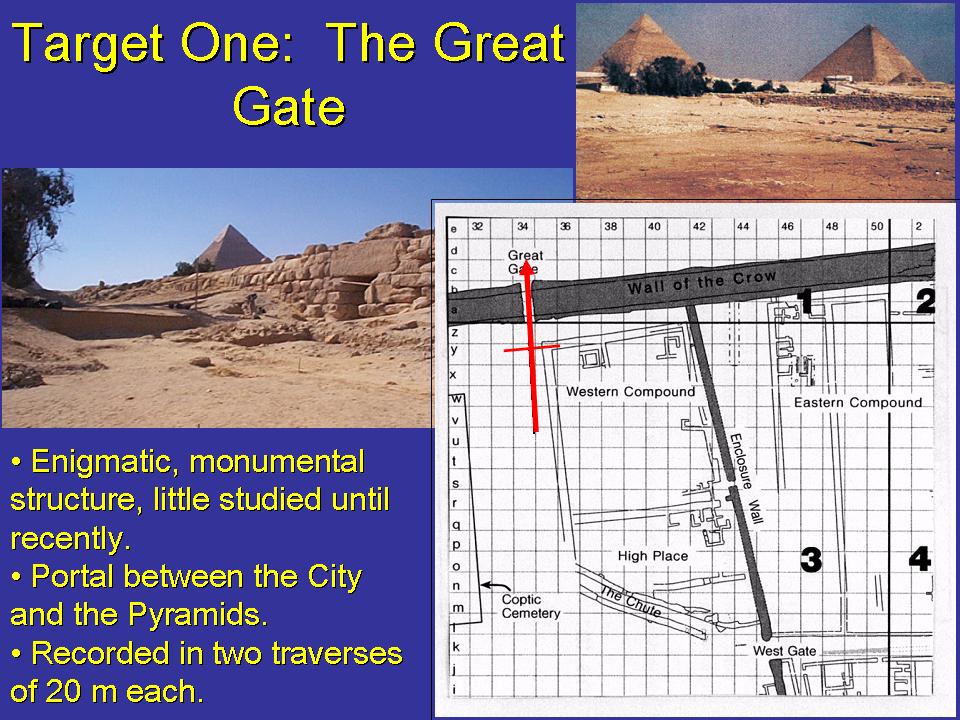

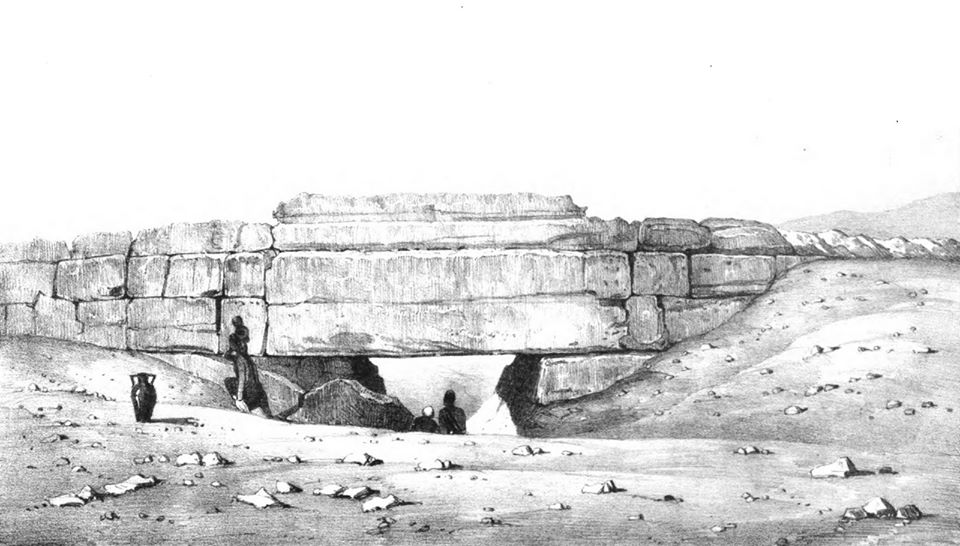

THE WALL OF THE CROWHEIT EL-GHURABGIZA

THE WALL OF THE CROWHEIT EL-GHURABGIZA,

EGYPT29° 58′ 19.50″ N, 31° 08′ 23.60″

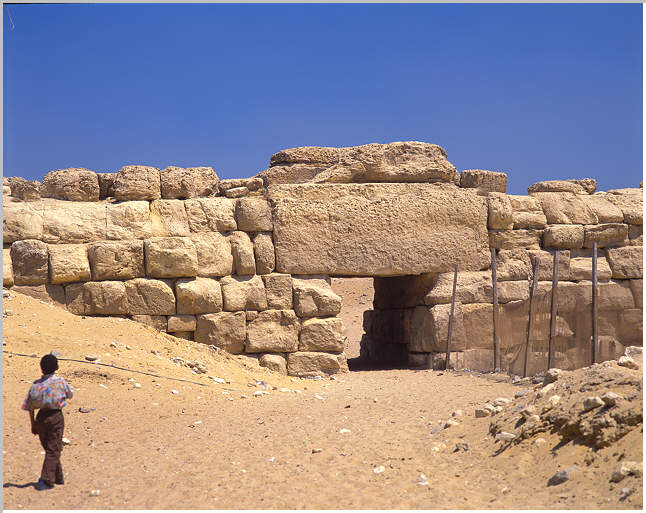

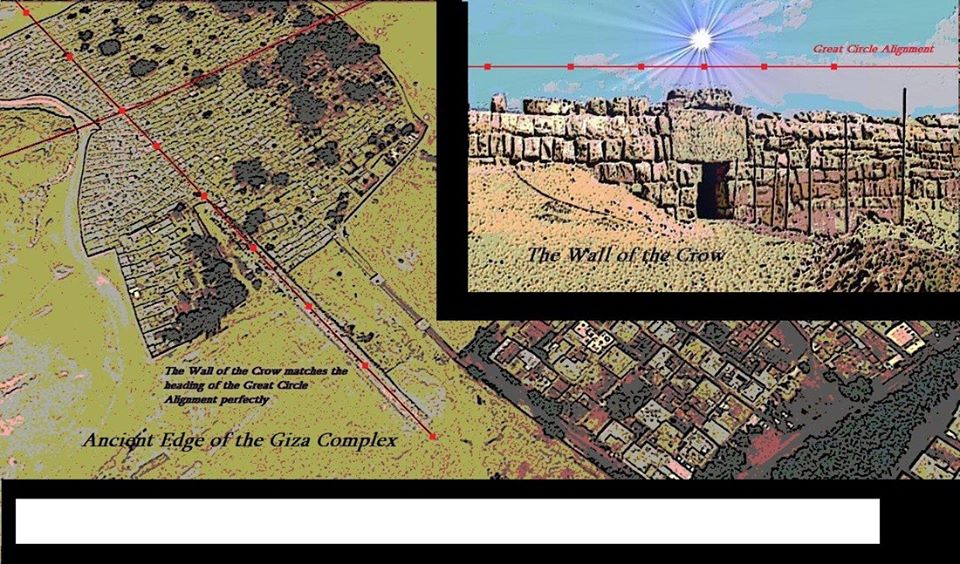

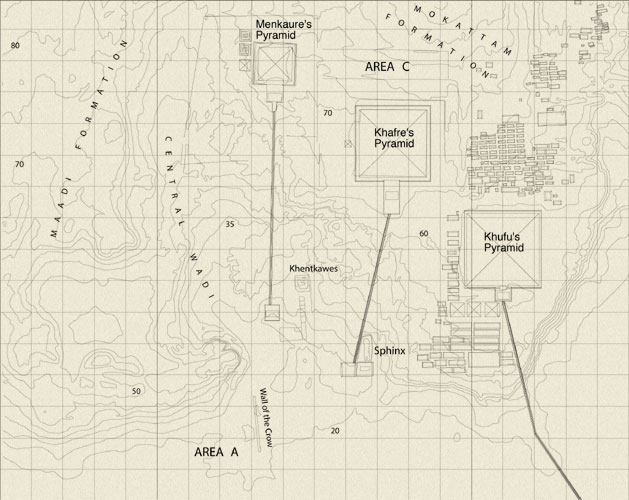

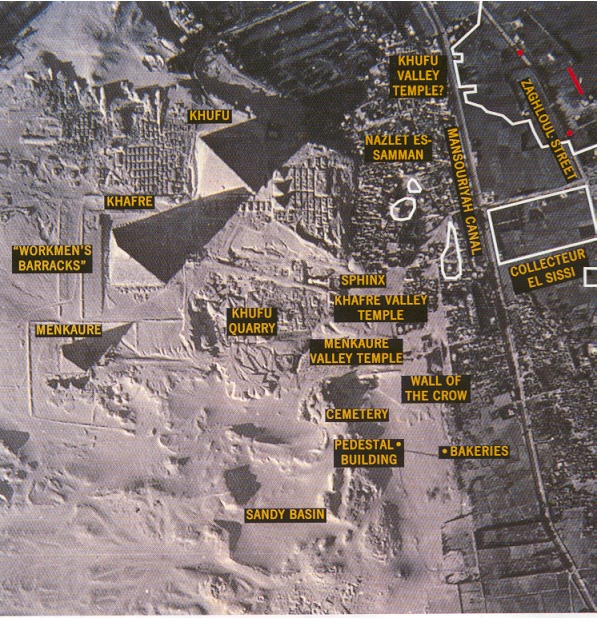

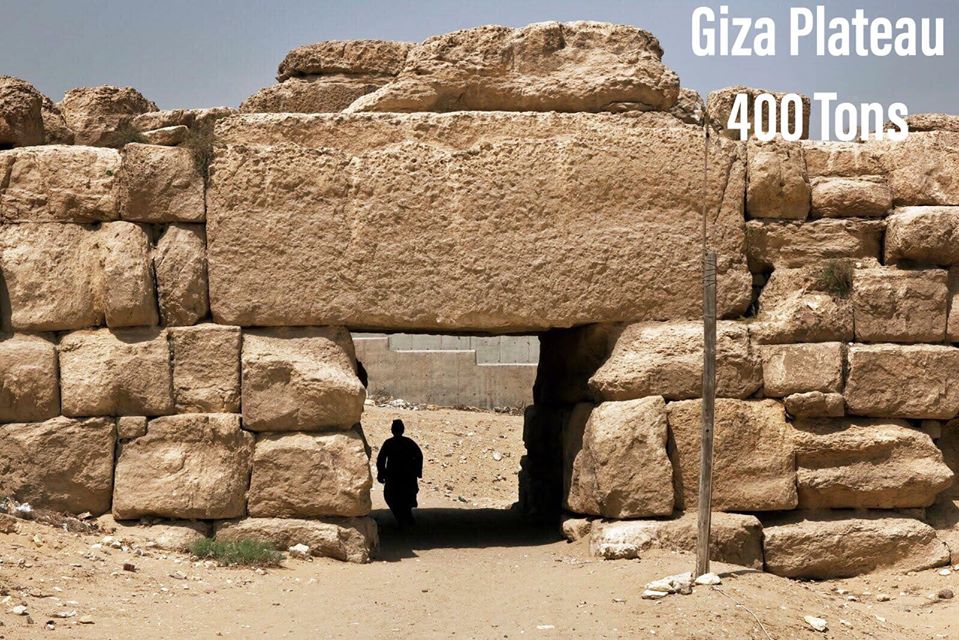

EThere is a massive, ancient stone wall that stands a few hundreds yards south of the Sphinx. But because it lay partially buried and overshadowed by the larger, more famous Great Pyramid, Sphinx, and other pyramids, tourists have hardly noticed it.Known locally as the Wall of the Crow (Heit el-Ghurab) it is 200 meters (656 feet) longten meters (32.8 feet) high and ten meters thick at the base. The Wall is the northwest border of a tract of low desert that we designated Area A

We suspected that the Wall of the Crow dated to the Old Kingdom 4th Dynasty (2575-2465 BC) like the Giza Pyramids and the Sphinx but we do not know why the Egyptians built it. Evidence suggests that they never completed the mammoth undertaking. They never dressed the masonry to produce a finished face to the structure, as was their standard practice with pyramids, tombs, and temple walls.We can now say for certain that the Wall of the Crow was built as part of our 4th Dynasty (2551-2472 BC) complexand the archaeology has led us to form some ideas as to its function.Gateway to the sacred?The great gateway in the Wall of the Crow may be one of the largest gateways from the ancient world. It has been visible for the last 4,500 years and yet very little has been written about it.Once we cleared away a thick, sandy overburden, we discovered what an impressive structure the gate is—2.5 to 2.6 meters wide (about 8.5 feet or five ancient Egyptian cubits) and about 7 meters (23 feet) highBecause the base of the Wall is more than 10 meters thickthe gate is actually a short tunnel.The ancient roadway going through the gate was paved with worn or abraded ceramic fragments and laid out with a subtle camber —

the sides slope down and away from the center — a common feature of ancient roads.Along the length of the south side of the wall east of the gate, we cleared a ramp-like slope on the surface of an embankment of limestone chips. This mason’s debris must have been waste from building the wall.It also may have been used as a ramp to drag the massive lintels up over the top of the gate.

After placing the stones, the builders left the debris immediately in front of and inside the gate. Upon this debris, traffic formed a path that slopes down 2 to 3 meters (6.56 to 9.84 feet) from north to south. The path passes through the gate to a broad terrace formed of compact sandy masons’ debris that extends at least 30 meters north of the gate.FunctionWall of the Crow in relation to Great Pyramid & other pyramidsWhy did the builders put so much effort into an immense stone structure that was not part of a pyramid complex nor connected to other structures at Giza?

The builders shaped and hauled a huge number of massive blocks to form something more like a dike than a wall. In contrast, the rest of our settlement is mostly built of mud brick or broken stone from the nearby Maadi Formation.

The Wall may have separated the sacred precincts of the pyramid plateau from the precincts in which the workers lived. The Enclosure Wall that bounds the Gallery Complex on the west nearly abuts the Wall of the Crow, and the regulated passageways out of the settlement—especially Main Street, the principle axis—led right to the massive gateway in the Wall of the Crow.Gallery set at the east end of the Wall of the Crow.In 2002 we found clear evidence that the Gallery Complex (at least Gallery Set I) predated the Wall of the Crow. Until then we were not certain where the Wall ended on the east. The eastern end of the Wall slumped in two layers of large stones, the result of collapse and robbing in late antiquity (we found Late Period burials under the lowest layer of toppled stones).The remains of the gallery walls were about waist to chest-high at the eastern end of the Wall, but about three meters to the east (10 feet), the gallery ruins were cut down to ankle level in a great depression.A massive deposit of granite dust and chips filled this big depression. The granite was from large-scale work nearby, possibly cuttings from the granite casing on the Menkaure Pyramid.But what force cut this depression through the mud brick gallery walls well before the end of the 4th dynasty occupation on our site? Perhaps a flash flood.Flood control?Geoarchaeologist Karl Butzer, who studied the environmental history of our site, believes that the 4th Dynasty Egyptians built their settlement on the outwash of a wadi, a stream bed that occasionally carried heavy floods running off the high desert.

The Wall of the Crow stands just to the south of the stream bed and could have served to deflect the floodwaters.Wall of the Crow near the Great PyramidIf the inhabitants built the massive stone wall for protection against desert flooding, why not extend it across the northern end of the whole Gallery Complex? Perhaps they thought that the thick, mud brick northern wall of Gallery Set I could withstand the wadi floods. The Wall of the Crow might then have been meant to protect the western flank of the Gallery Complex.In fact, an earlier settlement here might actually have succumbed to flash floods. In the lowest layers, those predating the Gallery Complex, we found settlement debris—mud bricks, pottery fragments, and limestone rocks—mixed with mud and pebbles washed down from the natural gravel in the high desert.We continue to look for evidence to support a hypothesis that the Wall may have served as flood-control to protect the workers settlement.Sacred structureLate Period burials sprawl in a large cemetery across the northwestern portion of our site, with grave upon grave cut into the Old Kingdom deposits. Toward the eastern end of the Wall of the Crow, the graves increase in density like the epicenter of a galaxy.Late Period burial near the Great PyramidThe Late Period (747-525 BC) residents of nearby towns must have considered the area around the Wall of the Crow as sacred ground. The burials extend right up to the east end of the Wall, with some of the dead interred in the sand above rocks that tumbled from the Wall. These burials post-date the collapse of the eastern end of the Wall.Caches of animal bone that we encountered in the same sand layer as some of the nearby Late Period burials are another sign of the Wall’s sanctity.One cache included two skulls—from a bovine and a smaller animal, possibly a goat. Another cache contained two cattle skulls. In the spring of 2000, when we began clearing the southern side of the Wall of the Crow near the east end, we encountered a third cache—a bovine skull and a Late Period amphora tucked into a niche between the blocks of the Wall.Next to the eastern end, the percentage of child burials is higher than in other areas: 60% compared with, for example, 27% in a nearby square.Many of these children were adorned with jewelry and amulets, while adult burials contained no grave accoutrements. We do not yet understand the significance of these special child burials.The Wall of the Crow todayThe area around the Wall of the Crow is still a burial ground. An Islamic cemetery engulfs the west end of the Wall and a Coptic Christian cemetery lies just south of it. During funerals, the deceased is carried in a procession through the great gate in the Wall.It is possible that this part of our site was a burial ground from late Roman to early Christian times. The first Muslim graves, the tombs of sheikhs (learned Muslim men) were built north of the west end of the wall.Both cemeteries—Coptic and Muslim—have wells; water sources are often associated with sacred traditions.The Wall of the Crow is also associated with fertility even today. Until recent years, women hoping for children would squat near a nail (a bronze survey peg pounded into the Wall by a surveyor many years ago), and then walk around the raised limestone blocks seven times.Through the millennia that the Wall of the Crow has laid half-buried, it has maintained its sacred aura and perhaps become even more mystical. We certainly look in awe upon this massive structure poised between the worlds of the living and dead, both ancient and modern.

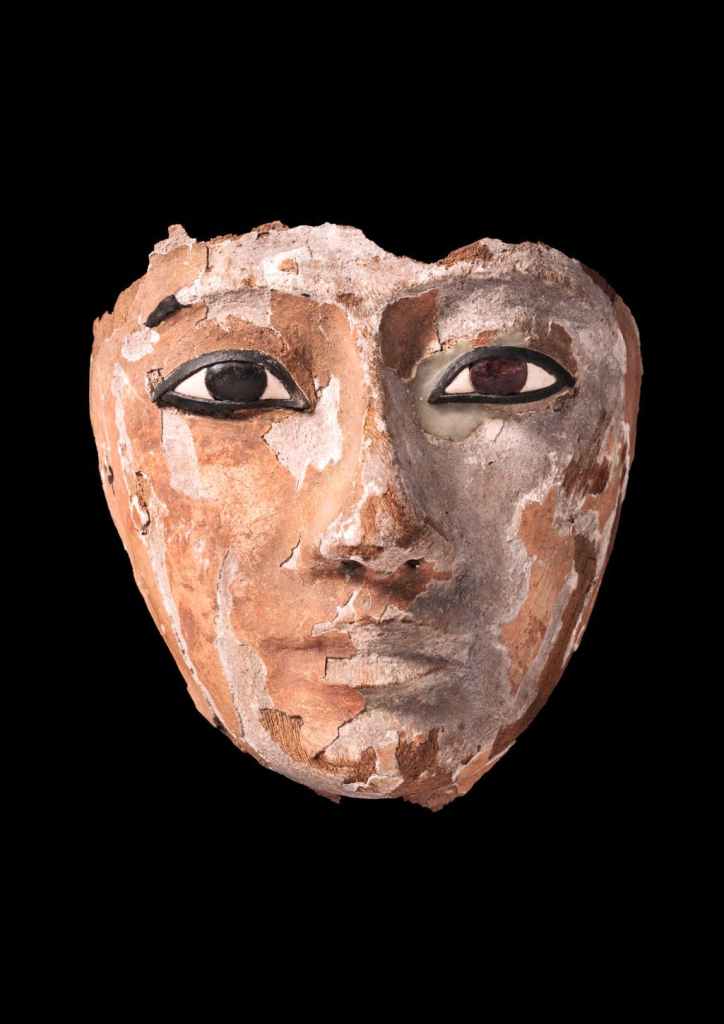

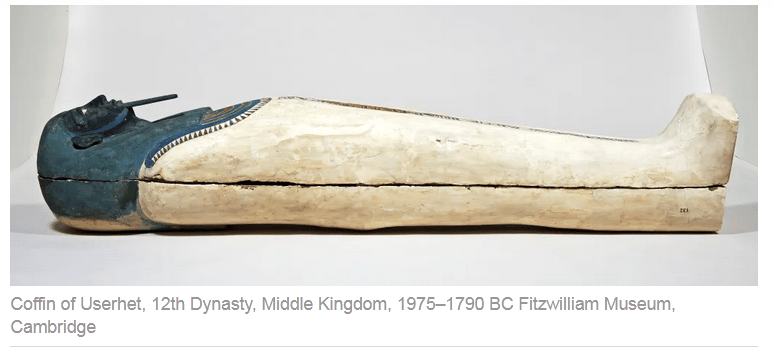

متحف المتروبوليتان يريد تحويل نظرتنا إلى مصر القديمة

أهمية الموت في الحياة المصرية اليومية

علم المصريات من وجهة نظر المصريين