Cities_Old_Egypt_3

_Atrib

14-4-2021

Province of Al-Galubeiah

Coordinates

30 ° 28′00 ″ N 31 ° 11′00 ″ E

Aribe is a small part within the city of Benha

Which no one knows about

Which had a high status in the distant and near past as it was a city of no less importance than the city of Thebes in the era of the Pharaohs, nor Alexandria in the era of the Ptolemies and the Romans

Then, with the passage of time, buried its history

Meaning of the word Atrib

I miss the word “Attrip”

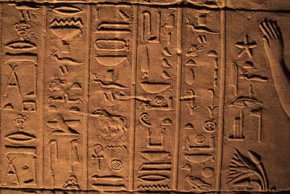

From the ancient Egyptian language (hieroglyphs), as its name at the time was “Hatt – Hari – Ibb”

Egyptologists have considered its meaning “the palace of the Middle Territory.”

Then the Assyrians, during their rule of Egypt in the late Pharaonic eras, derived the name “Hatrib” to indicate it

As for in the Coptic era, it was called “Atribi”,

As for the scientific community concerned with Egyptology, it is called “ATRIPS”.

It is the name given by the Ptolemies and the Romans during their rule of Egypt

In our research, we will refer to it by its Arabic name “Atrib.”

Omar of the city of Atrib

Egyptologists have confirmed that the history of the city of Atrib dates back at least to the Fourth Dynasty of the Era of the Pharaohs

It is a family that was founded by Pharaoh Senefru around 2613 BC

This means that the history of Attrib goes back to at least 4,500 years from now

As for the place of Atrib in the administrative division of the Delta in that period of time,

The ancient Egyptians divided the delta into twenty provinces

Each province had a capital and a symbol indicating it

Atrib’s share in this division was that it was the capital of the tenth district,

The symbol of the province was the black bull, also called the great black bull

(kem-wer)

As one of the forms of the god Horus, the favorite deity of Etrib

The Religious Center of La Tribe in the Middle Ages

The ancient Egyptians worshiped a large number of gods

And each city or county had its favorite idol

As for the tribe as the capital of the tenth province or the province of the country as it was called

Her favorite idol was the god Horus

And the god Horus is the son of the gods Isis and Osiris

And they worshiped him in various forms

He saw him in the picture of a child with a lock of hair and a finger in his mouth, an indication that he is still in his childhood

And he put it in the image of a young man with the head of a falcon or a sacred bird, indicating that he is in the stage of manhood and youth

Etrib in the ancient Egyptian dynasties

The Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1780 BC)

A granite statue, 63.5 cm high, was found in Atripe

It is not an inscription, but the study has proven that it belongs to the Twelfth Dynasty

The statue is from the British Museum

The Thirteenth Dynasty (1786-1633 BC)

In Atrib, a stone tablet of the pharaoh “Sanakh – Tawi – Sekham Kare” was found in Atrib

In the form of a crested falcon receiving an offering from the Nile god

The painting is of a prince named Mary Ra, and it is from the British Museum

The Eighteenth Dynasty (1575 – 1308 BC)

Atribe was an active contributor to the monumental architecture of the Eighteenth Dynasty

Through genius and height, the fate of one of the sons of the city of Atrib, Amenhotep bin Hapu

He is considered by Egyptologists to be the most important civilian figure who occupies a prominent place in the Eighteenth Dynasty

Amenhotep bin Hapo Al-Atribi

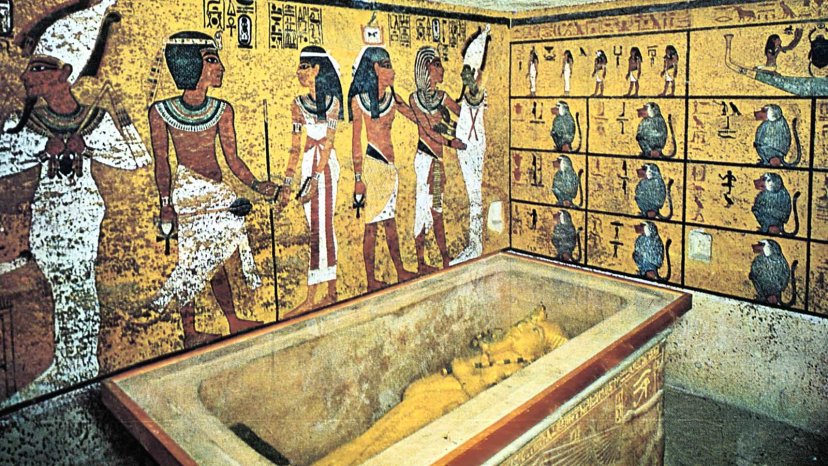

Although this family is rich with a group of the most famous pharaohs of Egypt, such as Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Tuthmosis III, Amenophis III, Akhenaten and Tutankhamun, the greatest of them in the art of architecture of his majesty is Pharaoh Amenophis III “1425 – 1375” BC,

It is also called Amenhotep the Third, the creator of the magnificent Luxor Temple, the colonnade of the Karnak Temple, the Rams Road between the Luxor and Karnak temples, the Colossi of Memnon and his palace in the city of Happi in the West Bank of Luxor, and its huge statues.

And all the great architectural facilities

Behind her is Amenophis III’s right forearm

The first question, designed and created, is Amenhotep bin Habu Al-Atribi

In this he says: The Pharaoh appointed me as director of his business in the Red Mountain quarry near Ain Shams, so I moved his huge statue that represented his pictures of His Majesty with all the accuracy of his art. I have to erect this statue in the temple of Amun, because he knows that I possess his hand forever

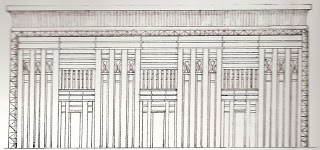

Atrip temple:

Egyptologists note that despite Amenhotep’s concerns and huge responsibilities in Thebes and others

He was fiercely loyal to his hometown of Attrib in the north

This fulfillment was marked by a practical method by asking the pharaoh to undertake architectural constructions in the city of Atribe

The Pharaoh responded and agreed to establish a temple to worship the region’s god, Horus – Khunta – Khatti.

An artifact bearing the name of Amenophis III was found in excavations in Atribe

It is believed that it was part of the temple wall

The Pharaoh gave Amenhotep bin Habu an honorary title, and he is “High Priest of Atrib”

Mister Breasted, an English Egyptologist, equated this title with the title Lord

That is why he was called Amenhotep bin Hapu, Lord of Atribe

The Nineteenth Dynasty (1308 – 1200 BC)

Ramses II is the most famous pharaohs of all of Egypt. Throughout his reign of Egypt over the course of 67 years, whether in his youth or in his youth, he made many great conquests and various facilities throughout the valley from its south in Nubia to the far north in the delta

As for his facility in Atribe, they were all destroyed by time and by the soft terrain

However, it was possible to infer it from what could be found from its remains, the most important of which are the following:

Two obelisks in Atribe In 1937, the German expedition, while excavating the hills of Atribes, managed to find a granite base for an obelisk attributed to Ramses II, and then they found a part of the obelisk itself.

As for the second obelisk, its base and part of it were found in some architectural buildings in the city of Fustat, the capital of Egypt, for use in building the city in the seventh century AD.

A blogger on Al Qaeda found information about Ramses II

As well as about the goddess of Atrib, “Horus-Khunta-my-sister”,

One of the two obelisks is currently in the Berlin Museum, Germany

As for the other with the two obelisk bases, it is located in the Egyptian Museum

Ramses II Temple:

The finding of the remains of these two obelisks indicates the presence of a temple in front of which these two obelisks were standing, but the German mission was unable to find evidence of that, but years later, the Liverpool mission managed to excavate them during 1938 to find this evidence, which is a base from a granite column One of the pillars of the temple engraved on it indicates that it is part of the temple

The mission also found a granite statue of a lion from the reign of Ramses II

It is currently the property of the British Museum

Stone painting of Ramses II with his son, Prince Merenptah:

In 1898, a stone tablet was found in the Atribe Hills, which had been deposited in the Egyptian Museum

It is an imperfect panel that was used in architectural processes

But after deciphering it, it became meaning to Egyptologists a lot

On the first side of the painting there is an engraved drawing of Ramses II offering an offering of bread to the god Ptah with the description of Ramses II with his usual royal descriptions behind him stood his son, Prince Merenptah, with his titles written as the chief of the army, bearer of seals, and the executor of his father’s orders. Merenptah makes offerings to the goddess Hathor, while at the front of the painting the titles of the pharaoh and the titles of the prince are written with the gods’ invitations to prolong life and to prosper in the country during the reign of the pharaoh

Scholars have noted that modifications that had been made to the painting are limited to

Addition of Prince Merenptah, who was making offerings to the gods. –

Removing some gods and replacing them with others.

A piece of the wall of the Atrip Temple:

In 1938, the University of Liverpool excavations found a piece of stone that was considered to be part of the wall of the Atrip Temple.

Two engraved images of tan were found on it, one of which was of Pharaoh Ramses II

He makes offerings to the goddess and the second to his son, Prince Merenptah, while he is doing the same work

ATrip Panel:

This painting was found in “The Red Kom” in 1882

It is a witness made of pink granite, two meters high, and written on its face an explanation of the wars that Merneptah fought against the enemies coming from the islands of the Mediterranean and with the Libyans coming from the west.

The words of the painting are located in 20 lines on the face of the painting and 21 lines on the reverse

The Twentieth Dynasty (1200-1090 BC)

After Merneptah’s death, the country prevailed for several years due to the internal conflict over power

Until this conflict was resolved by the Pharaoh Seth Nakhti, who was able to control the country

But his reign did not last long, so his son Ramses III came after him, who was more powerful and brave than him

Therefore, the foundations of the Twentieth Dynasty

Inhabitations of Ramses III of the Temple of Atrib:

It was stated in the “Harris Papyrus” that the works, grace and gifts that Ramses III granted to the Temple of Horus in the city of Atrib were mentioned without numbers according to the following text:

(Many blessings of sacred livestock were given to the god Father “Horus-Khunta-Khatti”, the god of Atrib, and repaired the walls of his temple and renewed it so that it became polished and multiplied the divine offerings, making them a daily sacrifice in front of his face every morning …. In the end, Ramses III concluded the text by clarifying the amendment that he introduced to the administration The temple against the corruptors and the removal of the minister who offended the temple, as follows

I watched the intruders, so I removed the minister who spoiled everything, seized all his followers, and promised the people who had been expelled from service, and thus the temple became like great temples protected from evil and forever preserved.

The Twenty-Fourth Dynasty (722-712 BC)

After the end of the reign of Ramses III, factors of weakness and decay began to creep in the country. Nine kings, all of whom were from Ramesses, ruled in a short period, and the last of them was Ramses the Twelfth. Thus ended the Twentieth Dynasty and the rule of Ramesses ended the country.

At those times, a strong and organized kingdom appeared in Nubia and took its capital, the city of “Nabta” near the current city of “Meroe”, and during the reign of its king, “Anakhi”, it began to march on Egypt from the south and seized Taiba, Manf and Ain Shams, and became on the outskirts of the delta.

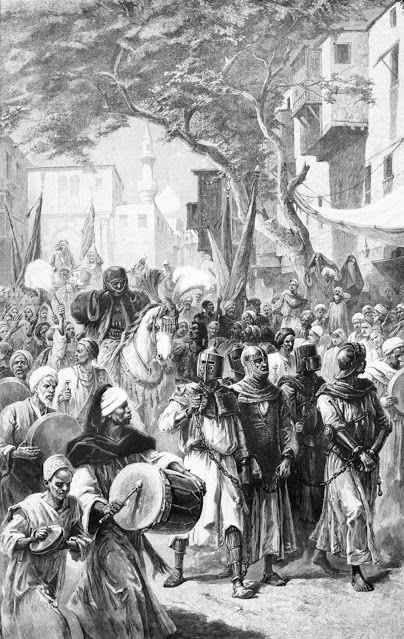

The arrival of the king in Ankhi to Atribe:

And Ankhi began to march north to seize the delta, where the princes who would rule the north of the country could be ruled

Its first direction was the city of Atrib, the capital of the tenth district, and it had its powerful prince, Buddy Isis

And when the princes of the states felt that the end of their king was approaching and that the fight against this king was about them being eliminated, the opinion settled with them that they would meet in Tribe with its ruler to present to this king the obligations of obedience upon entering Tribe

Treaty of ATIB

The king accepted to visit Atrib and to complete the ceremony of the treaty between him and the rulers of Atrib and Lower Egypt

The first thing he visited was the temple of the god “Horus – Khenti – Khatti”

He presented an offering to him, then he went to the seat of government in Atribe, where the kings and princes of the Delta met him, headed by King Osorkon, and all of them fell down before him prostrated

The Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (712-654 BC)

After the agreement was reached in Atrib, the king returned to Ankhi, to the capital of his country, Napa

But soon the Prince of Sayis rebelled against him in the western delta, and other princes of the delta followed him, and soon the country disintegrated again, especially after the death of Ankh.

Then came King Shabaka, who took over the king of his country to succeed his brother in Ankh, and extended his authority over Egypt

Then he undertook great works towards various temples

In Atribe, he found artifacts bearing the name of his coronation, which indicates that his works have reached this region

However, a new power appeared in the east of the country, the Assyrians

Who soon seized the Levant and threatened the country from the east

But due to the wisdom of Shabaka, there was no confrontation with them during his reign

Rather, the confrontation occurred after his death between Taharqa Ibn Ba’nakhy and the Assyrians

Then they were completed after his death, Tanub Amon, his nephew, who fought many battles with them under the leadership of their leader Ashurbanipal.

Who won some of them and defeated others

The wars ended with the return of Tanon Amun to his country’s capital, leaving the Assyrians to wreak havoc and plunder in the country.

The ruler of Sais facilitated their mission

Assyria rewarded him for that by making his son Ibsamatek the first ruler of Atribe around 663 BC.

Rather, the entire province becomes his fiefdom, which he controls as he wishes

These events were mentioned in hieroglyphic language

On Tanube Amun’s painting “Dream Board”

Exhibited on the ground floor of the Egyptian Museum

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty

But Basmatic, the governor of Atribe, had also been assigned to the principalities of Sais and Manf

And then he became of great influence, especially after the death of his father, Prince of Sais

He had the opportunity to be preoccupied with the Assyrians in the war with Babylon, so he took advantage of this opportunity and expelled them from the country and set himself up as Pharaoh over Egypt, north and south.

Thus, historians considered him the founder of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty

He was known as the first epsmatic

The fact of the matter is that Egypt lived in the era of a bright era that it had not lived for several centuries, and historians have considered that the glory of ancient Egypt and the height of its affair and its civilizations had returned again with the beginning of this family,

And Ipsmatik the first ruled the country from the capital of his king Sais in Lower Egypt, and his reign was 54 years

As for his son Nekhau, he ruled the country for only 15 years

Then came the second Basmatek Ibn Nekhau

Who had a strong connection with the city of Atrib, confirmed by the following disclosure

Queen Tachot, wife of Basmatik II, in Atrib

: Serendipity alone was the main reason for this discovery. In 1949 AD

Some peasants from Atrib found a granite sarcophagus while they were working on repairing a plot of land that was part of Tell Atrib, and it was revealed from the inspection that on the coffin the name of Queen Takhut, one of the queens of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, although it was not apparent at first sight that the owner of the mummy is the wife of Basmatic II except That it was confirmed later that this was compared to the coffin that had been found in the Ramesseum temple at Thebes of his daughter, called Ankhs Nafar An Ra, and written formulas on it were written confirming her lineage to her father, Pharaoh Basmatic II, and to her mother, Queen Takhout.

As for the wording written on the sarcophagus of Queen Takhot, which was found in Atribe, this is the text:

“He decided that the king would present it to the first minister of the people of the West, and to the great God, the Lord of power, to give an offering of incense and perfumes. Everything is beautiful from which God lives to the spirit of the hereditary princess.

“

As for inside the coffin, the mummy of the queen was hidden in it, and it was completely embalmed

It also had a collection of funeral and traditional jewelry,

The coffin and its contents were deposited in the Egyptian Museum

King Ahmose II (570-526 BC)

After Basmatic II came his son, King Abris, who increased his dependence in the army on foreigners, increasing their influence and not surprising in that he himself was a foreign descendant, but a man from among the people who held the position of army chief named Amazis was able to end the rule of Apres and set himself king of the country and continued The rule of 44 years

The country rose in his time in a great renaissance, so its prosperity and growth increased, and he was interested in constructing luxurious buildings and various temples, and to his reign some relics go back. In England

And that the most important thing that was found was a sarcophagus that the king made especially for the temple of Atrib

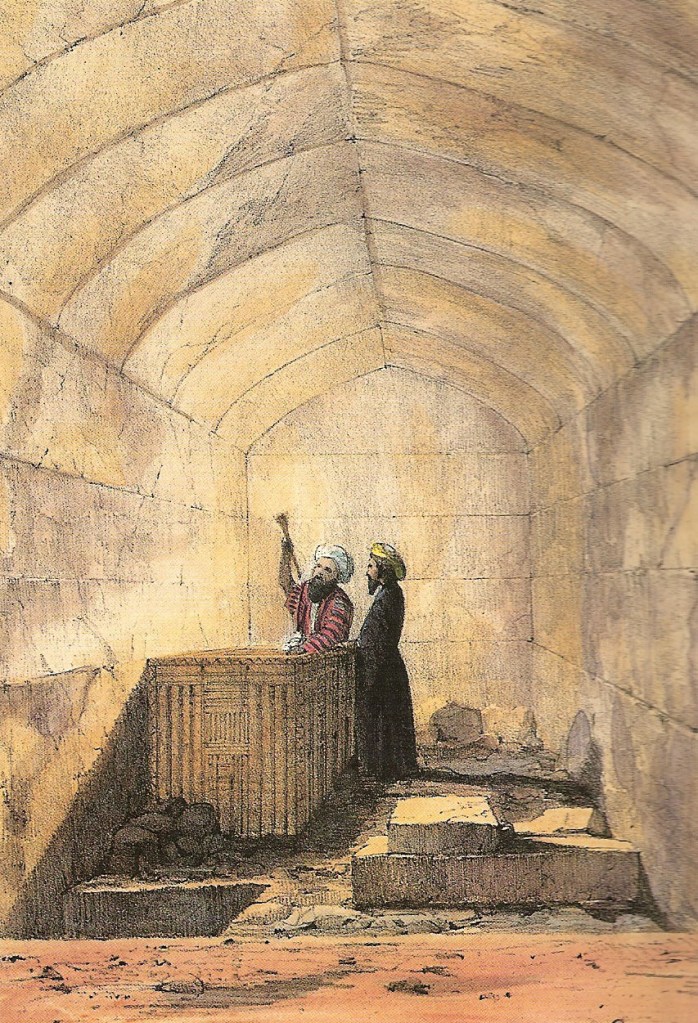

The sarcophagus temple atrip:

Some archeologists call the naos a deep roofed mihrab in which a statue of the god is placed in the temple and usually it consists of a single stone or granite piece whose dimensions differ according to the interest and ability required to manufacture it, and no one was allowed to enter the naos except for the most senior clergymen, as the naos had a door that closed on a statue of the god and placed In the most holy of holies in the temple

The first sarcophagus:

This naos can be found in the Louvre Museum in Paris

It is a single piece of granite and it was found in the sea in Alexandria

It is clear in its inscriptions that it was located in the temple of Atrib, to worship the god “Horus Khunta Khatti”

The sarcophagus was dedicated by King Amazis to the god Osiris and to his son Horus

The second sarcophagus:

This sarcophagus is in the Egyptian Museum and was found in 1907

Nothing remains of it except its ceiling, and the image of the ceiling shows the magnitude of the naos and the accuracy of its work. It is of granite granite and was given by King Amazis to the god “Km-Ro” (the black bull). On the outer wall on the right is a horizontal line that says: Long live Horus, the king of the tribal face Al-Bahri and he made it as a remembrance of his son (Kam-Ro), the greatest god

Attrip treasure:

Etheroin coined the term “trap treasure.”

According to the discovery encountered at Tel Atrib on September 27, 1927

When some farmers were reclaiming some land on the hill,

And they launched this name because of the huge amount of silver that Anitan contains from pottery

And its weight reached about 50 kg

Atrib in the Ptolemaic Roman era

The share of Atribe from the archaeological discoveries of the Pharaonic era far exceeds its share of the Ptolemaic Roman era, and the reason for this may at first glance be the length of time that Atribe lived

In the first era, when it reached 2290 years, i.e. from the fourth dynasty to the Ptolemaic era (2613 – 322 BC)

For about 960 years, i.e. from the Ptolemaic era to the Islamic era (322 BC – 640 AD)

In the second era, or the reason for that may be the type of rulers of the first era who are known for their Egyptian affiliation with the people of Egypt and the soil of Egypt. They are its people and its people, except for a few extraneous ones.

This is in contrast to the type of rulers of the second era, as they were strangers to Egypt, either from the Greeks or the Romans, and all of them looked at Egypt and its people with the view of the exploiting colonist who focused his activity on the reconstruction of the country to the extent that it would benefit him and take its benefits

Despite the small number of archaeological discoveries for the second period

However, what was revealed from it clearly reflects the nature of social, economic and political life in Egypt

And its implications for life in the city of Atrib

Atribe under Ptolemaic rule – 322-30 BC

Ptolemaic rule of Egypt began about ten years after Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 BC

As after the death of Alexander in Babylon in 323 BC

The empire was divided on itself, so Ptolemy, one of his leaders, ruled Egypt in 322 BC

Thus began the rule of the Ptolemies of the country from the new capital Alexandria, starting from Ptolemy the First to Queen Cleopatra. Ptolemy the First ruled Egypt for nearly forty years, during which he laid the foundations to ensure the continuation of the rule of his family after him, and the exploitation of the country’s wealth for the benefit of them and his Greek and foreign followers with continuity and benefit.

In the early days of Ptolemy’s reign, a powerful religious figure appeared in the city of Atrib

Derived from the power of Ptolemy, the ruler of the country, the name of this character – ZHare

Zhair, nicknamed the Savior:

All the information about this character is derived from a statue of him found in September 1918 near the Coptic Cemetery in the village of Atribe. It is made of black granite in fine manufacture and in excellent condition and dates back to the era of Ptolemy I.

The statue consists of two separate pieces

First

It is a statue of Zed Hare, the owner of the statue, while he was sitting cross-legged with his hands bent on his knees, and he wore a robe engraved on it and on every place of his body the words of a hieroglyph

As for his legs, there is a vertical panel, which is part of the statue, with a drawing of the god Atrib, “Horus, my sister, my sister.”

He is in the image of a child standing with a braid of hair hanging on his chest and standing on a crocodile

As for the second piece

It is the base of the statue, but it differs from the usual in that it has a gap in which the statue is fixed, so that most of the base becomes in front of the statue and is engraved with channels that end in an oval-shaped basin for the water to settle in. The statue was deciphered and explained by the scholar, Egyptologist Miso Darsi, and Darsi says in his research that the statue is a wonderful piece of art, as well as the texts written on it are a new addition to our information about the ancient Egyptian religion.

As for the owner of the statue, it is of a civilian man who made a statue of himself in pride, vanity and vanity

But it goes back and says that it was commissioned by King Ptolemy the First

He also commissioned him to build a temple in Attrib, to the south of the original temple

From one of the statue texts:

I am the faithful to Osiris, the master of (at-quantities) and (Rosati) the two holy ones located to the south and north of Etrib and I am the guard and responsible for the gates of (Horus, Khunta, my sister) and the chief of Atrib, who is in charge of the sacred birds.

And about recording everything related to her, I am the savior.

And that all the texts recorded on the statue and its base in which Zed Hare speaks about himself as if he was the first and last administrator in the affairs of the city of Atribe and in its temple, and he mentioned his family names and also the name of the example for which the statue was made

Finally, it was found that this statue was used in religious rituals

This is to pour water over it and use the water collected from it in the basin for healing

And to receive blessings from the gods through the savior Zhair

Remains of a burning building in Atrib:

The Polish expedition reached during its excavations around Tell Sidi Youssef in Atrib, which took place in November 1985

From the discovery of the remains of a building built in the third century BC, that is, in the Ptolemaic period

It has burned from about the beginning of the first century BC

The mission determined the location of the building and the effects it contained by using the method of change in the electrical resistance of the components of the earth. It was also able to determine the date of the fire by applying the radiocarbon theory to the carbon components of the charred wood pieces.

As for the contents of the building, the mission found the remains of many statues of the Greek god Aphrodite

What the mission considered to be an indication of the influence of Atribe at that time with the Greek religion. The mission also found many remnants of pottery and ceramics made or imported from southern Italy.

It dates back to the second and third centuries BC

This view was also confirmed by finding among the contents of the building coins dating back to that period of history

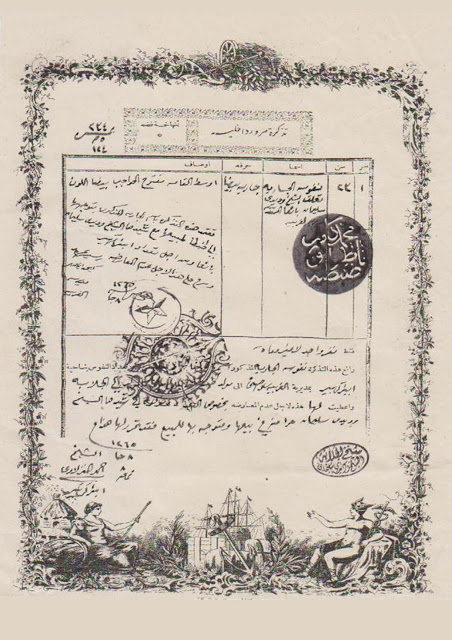

Refugee protection right for the Atrip Temple:

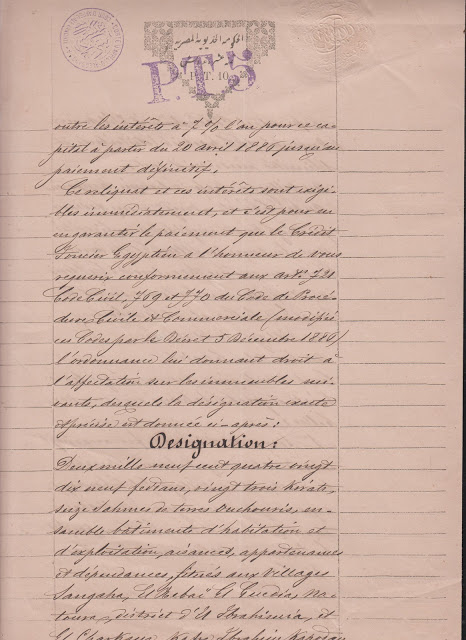

After about 200 years of the rule of Ptolemy the First, conflicts, weakness, and mismanagement were characteristic of the rulers of Egypt from the ptolemies, and therefore their closeness to the people of the country increased through priests and clerics who could control the people. BC

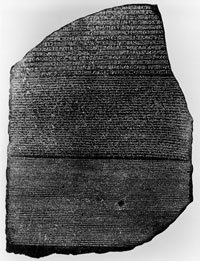

These authorities stipulate that the king gave the temple of Atribe the right to protect those who resort to him, and it is a protection above the law that makes the refugee to the temple immune to any rulings issued against him. Trilingual stony is Hieroglyphic, Democrat, and Greek

Atribe under Roman rule (30 BC – AD 640)

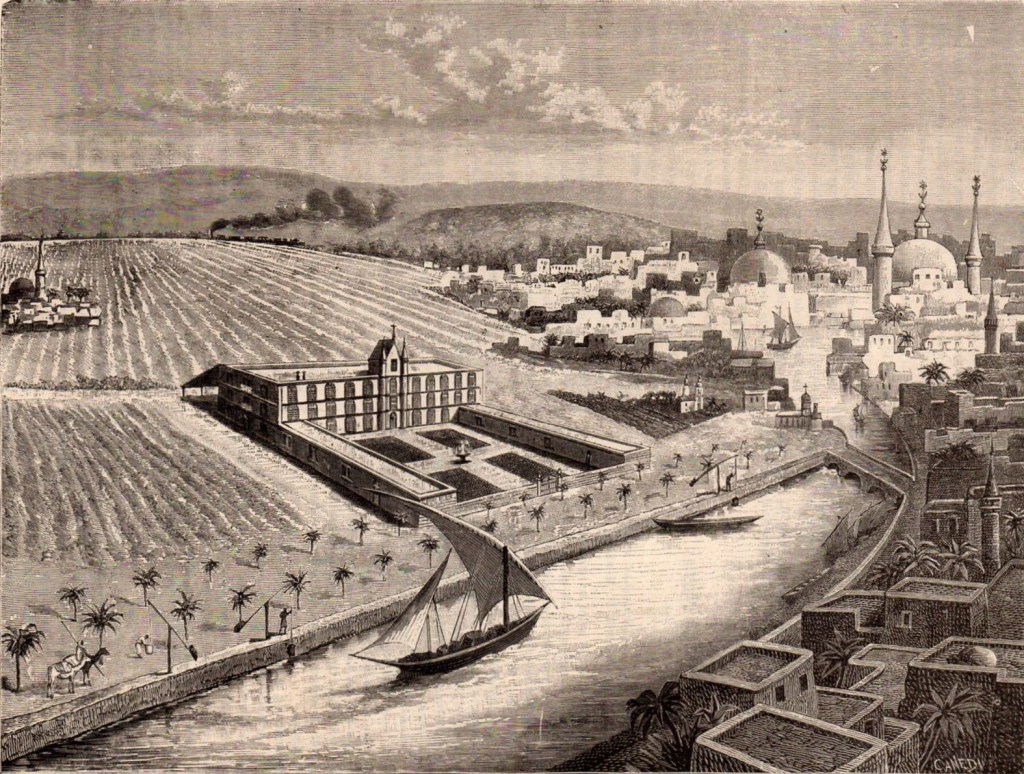

Egypt was at the end of the Ptolemaic rule in its worst economic and political conditions, which paved the way for the Roman occupation of Egypt in the year 30 BC. With the entry of the Romans, they focused on internal reforms such as reclamation of arable land with the improvement of agricultural methods by cutting canals and clearing canals. The capital of one of the regions of Egypt, and for its existence at the crossroads of several roads within the agricultural area

This was proven by the Liverpool mission in its excavations and studies in Tel Attrib during 1938, which is as follows

A system for the delivery of drinking water to the city of Attrib:

The University of Liverpool mission found an integrated system with a high level of accuracy to deliver drinking water from the Nile to the city of Attrib, as it consists of a group of water channels roofed with red bricks and connected to each other with small and open wells to extract water, and these wells are used at the same time as connections between the channels branching from them.

The mission noticed that the canals are in good condition and parts of them are still working, and the measurements of the parts that were studied on the ground are a covered part about 18 meters long.

It is located at a depth of one and a half meters from the surface of the earth and its walls were 40 cm thick and 180 cm high

Social life and population density:

The University of Liverpool mission noticed the enormity of pottery remnants in the ruins of Atrib, in addition to a group of statues, scarabs, and sound-lit pathways. It also found a large number of Roman tombs known with their domed ceilings. This indicates that this city was very populated at the time.

Dr. Karol Muslevik, head of the Polish mission, confirmed that the archaeological references issued in Italy on the history of the Roman Empire mention the city of Atrib in the Nile River Delta

However, it was one of the four large cities of the eastern Mediterranean countries

It depends on it to supply it with various products

The inhabitants of the city of Atrib were made up of two classes, the foreigners and the Egyptians

Arc de Triomphe

When the University of Liverpool mission carried out its excavations in Tel Atrib in 1938, it found a part of the Arc de Triomphe in the form of a Roman-style square gate dating back to 374 AD and it has a gift written in Greek to three Roman emperors. Who did the work

Roman temple Patrieb:

The Liverpool mission also found the remains of the Roman temple that was standing in the city of Atribe, and the mission determined its location from studying the remains of the marble columns and some of the remaining parts, but could not continue the excavation because the rest of the temple was located under the new road extending from the conciliatory wind to the new Benha Bridge (at that time). Maqam on the Nile

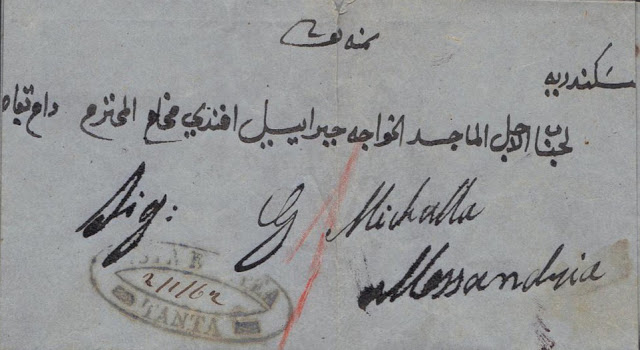

Attrib from the Islamic conquest to the French campaign

I see the compromise plans

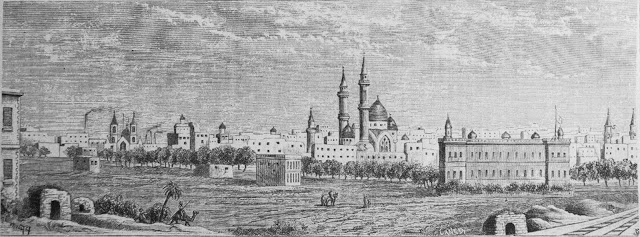

Description of the city of Atrib:

It came in the description of Atrib, quoting Iyas, Ibn Kinda and al-Maqrizi, and what was mentioned in the books of the following Franks:

“Attrip is from the great cities on the shore of the Nile, and it is called” Atrips “, its length is 12 miles

It also had twelve gates, and it had a bay in which the waters of the Nile flowed from which small canals branched from which it carried water for the dwellings, and its houses were very good and its largest street was perpendicular to the Nile line and had a brilliant park and a street smaller than it was perpendicular to it penetrated the south and north

As for its urban features, it was mentioned in the following plans:

- In Atribe, there was a monastery for the Virgin, known as the Monastery of Mary Mary, located on the coast of the Nile near Benha

An annual feast was held for it on the eleventh day of Baouna, as it had a bishopric and a house for the rulers to reside in the provincial capital Atrib, which was followed by many villages that reached one hundred villages and eight –

As stated in the compromise plans

Also, Al-Maqrizi was quoted in his letter on the Arab tribes from Yati

Atrib was among the cities that the Arabs settled in, and the people of the city used to dig in its hills, and if they found marble or stones in it, they made joints to build from it, and accordingly they found many ancient things with traces of domed graves resembling the graves of Muslims

The story of the attempt to burn Attrip:

Came in the compromise plans, quoting the historian Tariqa of Alexandria

When the Caliph learned that the French armies had arrived in Parma in the east of the country, he directed a campaign of soldiers in boats to the maritime authorities and ordered them to burn whatever they found useful to the enemy, including ships and supplies, and he also sent another load by land, whose mission was to hinder the advancement of the enemy and burn everything they find useful for them. They carried out what they were ordered in the farms, villages and cities on the way

Their path

And when they reached the city of Atrib and were about to burn it, they were terrified of what they would commit, given what they saw of the goodness of the city and its order and the five waterways in it, apart from the Gulfs, so they refused to implement their plan

The city escaped from burning

The holy bird returns to Atribe:

Before the Egyptians converted to Christianity, Latreeb was her favorite deity, Horus

One of his pictures was a white bird in the shape of a gentleman, and that is why the people of the Attrib district considered him a sacred bird

They took care of him and performed his ministry, which was undertaken by the priests and servants of the Temple of Atrib

In South Attrib, he had a private barn for him called (At – Kimat)

In it, his offspring is hatched, cleanliness is carried out and food is provided to him

We go back to what came in the conciliatory plans for those who preceded him, who brought them

A white dove comes every year on a specific date during the celebration of Saint Mary’s Day in Atribe

She enters a monastery and settles on the altar and stays in its place for several days, then leaves and does not return

Except on the same day of the next year in the Coptic calendar

Muharram Kamal comments on this event in his book

“Traces of the Pharaohs civilization in our current life”

That what is happening is an extension of what was happening in Atribe of reverence for this bird in the past

Atribe was worshiping the god Horus, who was represented by this bird

The deterioration of the conditions of Atrib:

Although the city of Atribe was at the beginning of the Islamic conquest an extension of the Roman system, as it was the capital of a large administrative region, as it is described in the book “Description of Egypt” of the French campaign around 1800 AD, that is, after about 1160 years

From the end of Roman rule, Atribe was a village belonging to the Eastern District, and it was located on the edge of wide hills of an ancient village bearing the same name, which was in the past one of the holy cities in ancient times.

Thus, it became a normal village belonging to others, and thus its luck was forgotten

As for when this neglect happened to her, it came in the Geographical Dictionary of Professor Muhammad Ramzi

That this happened in the seventh century AH, starting from the Mamluk era

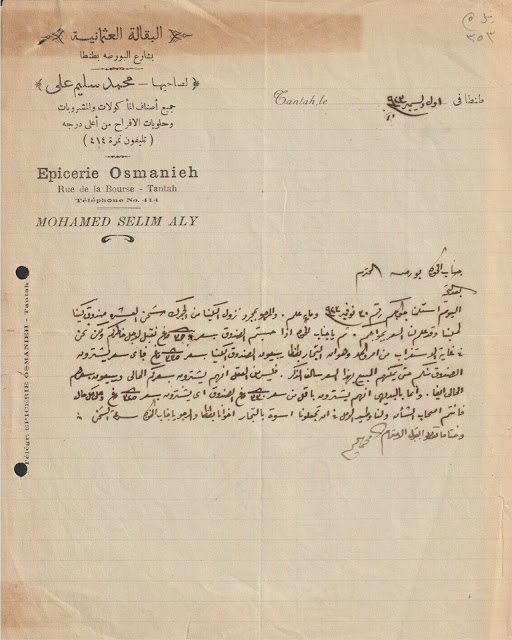

Atrib in the era of the family of Muhammad Ali Pasha

The deterioration that occurred in the Pharaonic city of Atribe during the Mamluk and Ottoman eras

Its features appeared in the decline of the lands of Tel Atrib, as it was mentioned in the geographical dictionary, citing victory and masterpiece

The financial unit of Atrib, as it was mentioned in the money books in the old documents, amounted to 758 acres, after which it was mentioned in the conciliation plans that the area of these hills during the period of Muhammad’s rule over Pasha and his family until the date of issuance of the plans around 1886 CE was about 300 acres, then this amount decreased and arrived in 1900 M to about 200 acres

Only as stated in the geographical dictionary

Although Atrib had become during the French campaign one of the villages of the Eastern District, the village affiliated to it, which was Benha, was separated from it as well.

It came in the book describing Egypt for the French campaign

There are two villages in the vicinity of Tereb, belonging to the Qalyubia governorate, one of them is Kafr Benha (Abu Zikry) and the other is Banha Al-Asal

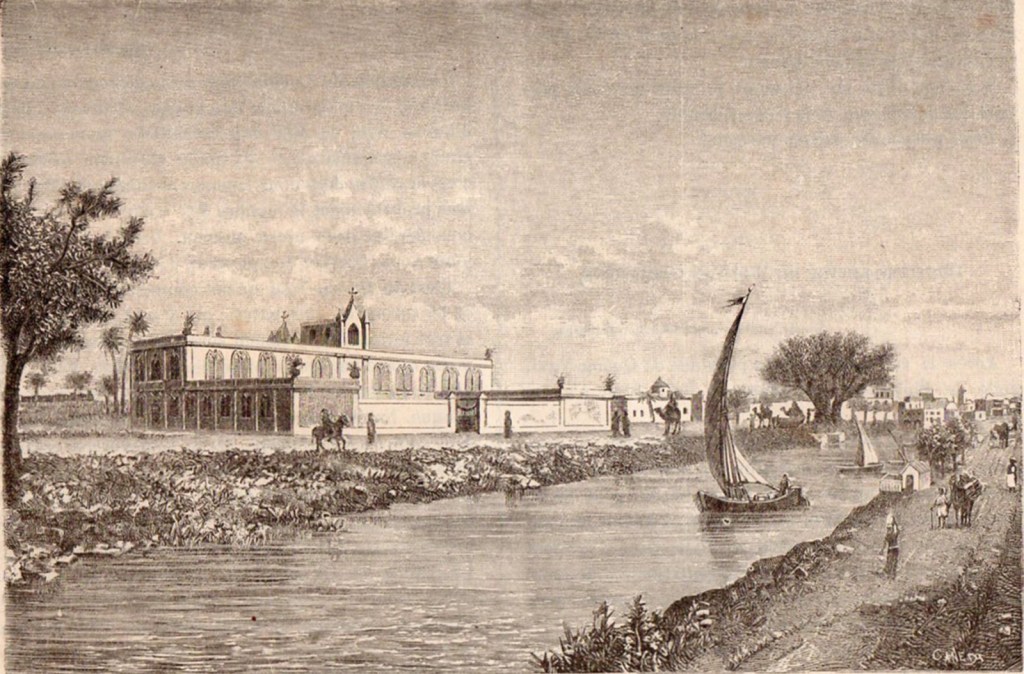

Abbas I Watrib (1849-1854-)

When Abbas I took power in 1849 AD

He built a palace for him on the Nile in Benha Gharibi, the ancient Tel Atrib, while the village of Atrib was located to the east of the hill

Accordingly, the Atrib hills were located between the west and the village in the east

Abbas I was known for his volatile mood, and he did not like what he heard about the conflicts in the village of Atrib, whose effects extend to the roads of the hill and among its ruins, which was a shelter for the disputants, so he decided to move Hali Atrib to another place several kilometers to the east, and the people of the village lived in a place called the same one, which is near the village Dead sebaa

The rule of Abbas I did not last for long. After his assassination in his palace in Banha, for several years, the people of Atrib sought from the administrative authorities to return to their original home, Atrib, so he allowed them to do so, and there were still two villages with the same name. West Half Atrib or Tel Attrib

Benha Watrib

On the contrary, what happened to La Trib, an improvement in Benha’s conditions

Which was nothing but two small villages, Kafr Benha and Banha Al-Asal, belonging to the Qalyubia District and its capital, Qalyub.

So Abbas I issued a decision in 1850 AD to make Benha the capital of the Qalyubia District instead of Qalyub

This is until it takes a better administrative situation to suit the presence of the king of the country in his palace in Banha and what he needs in terms of reception, hospitality, and services for the palace and the courtiers. The western village of Tal Atrib, belonging to the Eastern District, continued until a decision was issued to transfer its subordination with some of its neighboring villages to the Qalyubia District, thus the village of Atrib became one of the subordinate villages. For the city of Benha

Aitrib in the contemporary era

We are now at the end of the Pharaonic city of “Hat Harra Ib”

Or the Egyptian Ptolemaic Roman Atrips

And it is, as archaeologists say, buried at different depths of the surface of the earth, because the nature of the land on which this city was based is composed of sediments of Nile River silt, which are soft, heavy deposits that are easy to dive into the depths of the earth.

This was confirmed by the excavations that took place in them, as their effects were found at a depth of more than two meters from the surface of the earth

On the surface of the land and in its place, urbanization has swept over the area from all sides. The Cairo-Alexandria Agricultural Road was established, which bisected the hills of Tell Atrib into two parts, one in the north of the road and the other in the south of it.

And when the headquarters of Qalyubia governorate and its administrative, cultural and other apparatus were moved to where Abbas was the first and the construction began to gradually move towards areas of Tal Atribe, the sports stadium was established, hospitals and Benha University buildings were established, and many residential constructions were made so that a few years did not pass until the archaeological sites of the city were completely finished and nothing remained The archaeological area of Kafr El Saraya is next to Atrib and three small hills, the largest of which is used as a Muslim cemetery

As for the other two, they are known as Tal Sidi Youssef and the other, Tal Sidi Nasr

And now the curtain has fallen on the ancient city of Atrib

Other people or dynasties of its former people now live on its ruins and have been swept away by the current of life

Today and tomorrow’s problems overwhelm them, so they don’t have the opportunity to look back to take a lesson

Or searching for the roots for inspiration

And how many people in the world today are looking for roots and not finding them at all

So they try very hard to make for them a history that is a few hundred years old

Let them set them in mind, to be a beacon to illuminate the way for them

Sources

The End of a Pharaonic City / Written by: Al-Husseini Saleh

Year of publication: 1991 Number of pages: 92 pages